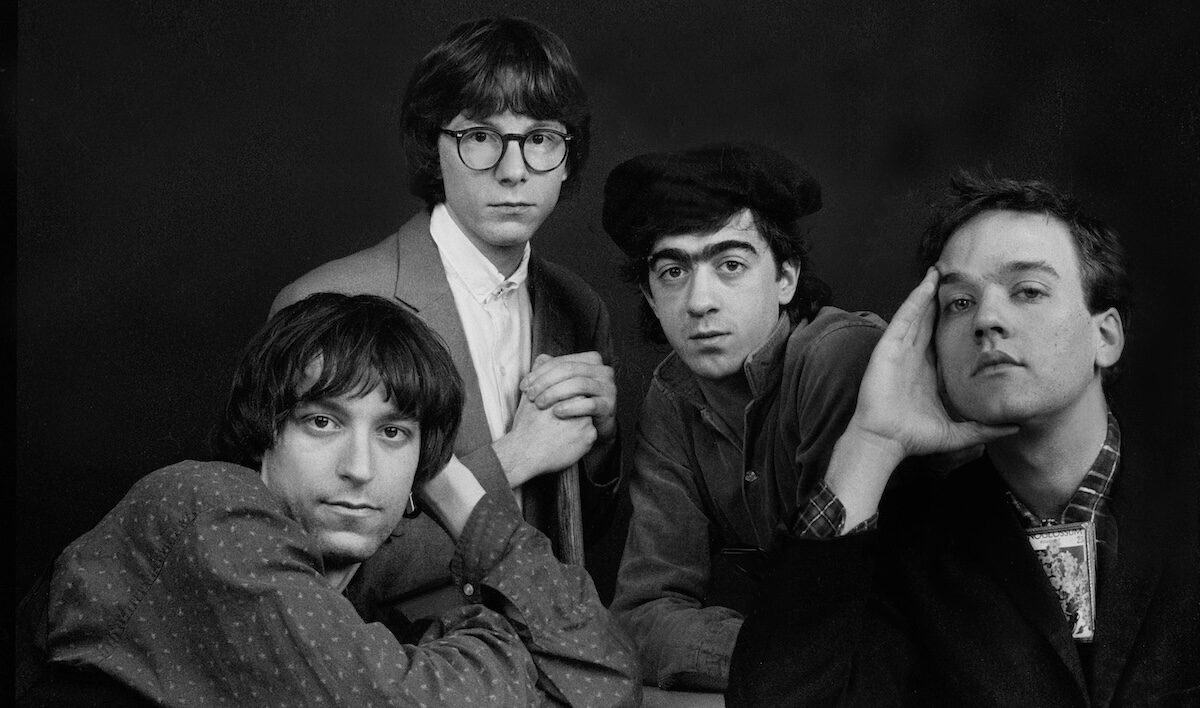

From Uncut Take 78 [November 2003 issue] Peter Buck, Mike Mills and Michael Stipe talk about the 20 greatest singles of their major-label era. But which one does Stipe find “gross and disgusting”? And why does Mills think, “It’s amazing how many songs we’re playing now that we could have written yesterday”?

From Uncut Take 78 [November 2003 issue] Peter Buck, Mike Mills and Michael Stipe talk about the 20 greatest singles of their major-label era. But which one does Stipe find “gross and disgusting”? And why does Mills think, “It’s amazing how many songs we’re playing now that we could have written yesterday”?

There’s always been a tendency to measure REM in terms of their albums. This is partly down to elderly, complacent notions of the relative ‘importance’ of albums over singles, representing as they do more sustained creative efforts, to be savoured in aloof privacy. What’s more, REM albums have often been statements of intent, their musical mood and implied manifesto instigated, as a rule, by Buck and often as a deliberate reaction to their previous work. For example, the rocky sleaze of Monster was a response to the gravitas of Automatic For The People, the friendly yellow-golden tones of Reveal an antidote to the experimentalism of Up, and so forth.

And yet, as if in defiance of themselves, REM are also a great singles band, a very public band with a knack of creating big, ear-catching anthems or, thanks to the distantly but unerringly sensitive Stipe, tapping into undercurrents in the collective mood and bringing them to the surface. It’s that REM which Uncut explores here as Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck discuss what we consider to be their 20 finest singles since making the fateful leap to Warners (the period covered by their imminent best-of) and rock’s major league. Even their brightest, daftest moment, “Shiny Happy People”, embarrassed as the band are of it, is one of the great earworms of the ’90s. Then there are singles like “Stand”, “Daysleeper” and “The Great Beyond”, each drawn from very different points and phases of REM’s history, yet each reminders of a quintessential thread that runs through their changeling career. That is, their unique, undiminished capacity to write loud, translucent, timeless, unaffected, deceptively complex yet instantly irresistible pop-rock songs, the sort for which the grossly over-used term ‘classic’ should be more strictly reserved.

Then there’s Magisterial REM, on singles like “Drive” and “Everybody Hurts”, in which, minus the ostentatious anguish or histrionic clumsiness of other would-be Keepers Of Rock’s Conscience, REM walk where others fear to tread in this inchoate, postmodern age, writing – whisper it – songs that matter.

Finally, we hope that whatever arguments you might have about the order of, and inclusions in, this Top 20, that there’s not too much grumbling about the No 1 – fittingly, it was undiluted Essence Of REM which would give them their massive breakthrough hit. So typically atypical. So REM.

20 SHINY HAPPY PEOPLE

From the 1991 album Out Of Time. Released: May 1991.

Chart positions: UK No 6, US No 10

Intended by Warners as a big play for chart success (they hadn’t figured on “Losing My Religion”), “Shiny Happy People” is one of REM’s most notorious and reviled songs. Comedian Denis Leary did a short routine to camera lampooning its happy clappy sentiments which was so heavily rotated on MTV that it threatened to rebrand REM as inane jangle-popsters. While some shuddered at the song, coupled with the video featuring guest artist Kate Pierson of The B-52’s bopping and cavorting joyously, it can be regarded, years on, as what it is – a consciously exuberant piece of bubblegum pop which, even minus any inverted commas, has an inbuilt irony. What’s more, elation is a more difficult emotion for leftfield bands to capture and sell to teen audiences than misery, so kudos to them for trying

MIKE MILLS: It’s not exactly the legacy we would have chosen for ourselves. Then again, it entered the lexicon and maybe there’s something to be said for that. But would we play it live? No. Never have and never will, I assure you. It’s not a bad song, I’m not ashamed of it. Once in a while you’ve got to write a happy song and that’s what that is.

MICHAEL STIPE: Denis [Leary] at that time was approaching me at dinners, saying it was a schtick, he was a fan of the band and I completely understood that. I wouldn’t say I’m embarrassed by the song, but it is what it is, it has limited appeal for me. I never bad-mouth – I try to never say anything bad about the songs that I don’t particularly like. Because there might be someone out there who hears that to whom that song means everything, to whom that song represents some moment in their life which is essential and I don’t want to take that from them. It is kind of a fun, stupid song if you’re six years old. I’m not getting defensive, I’m just saying, there it is, end of story. But I wouldn’t particularly want to sing it again.

PETER BUCK: I know Mike and Michael are embarrassed by “Shiny Happy People” but I’m not. It’s totally twee, but that’s OK. Even Led Zep sang about fairies and Tolkien. It’s just a small part of what we’ve done. I’d be happy to play it live just as a one-off but Michael and Mike wouldn’t agree. I don’t know why they’re so embarrassed about it. It seemed like I was doing it under protest at the time? Well, the video, yes, I hated that. They’re like, “And then you’ll dance.” “And then I’ll dance, my ass! It’s not gonna happen.” “Well, try to look like you’re having fun.” “But I’m not having fun!” In the end, they had to work around me and they managed to find one bit of me dancing, when I was actually making fun of Michael.

19 I’LL TAKE THE RAIN

From the 2001 album Reveal. Released: November 2001.

Chart position: UK No 44

The album Reveal was criticised for its lushness and blandness, often by those who equate ‘guitars’ with ‘edge’. “I’ll Take The Rain” is an example of the deceptiveness of what initially seemed like a commercially over-friendly album. While the rain motif is the thread that connects it to classic REM, it’s very much a song of experience born of age, wisdom and perhaps even fatigue, rising slowly but with dignity to its stoical crescendo.

PETER BUCK: Well, rain has a lot of signifiers, from puddles to cleansing. I don’t think rain is a bad thing, necessarily. And the spirit of acceptance in that song is good. In a way, it’s the same message my kids get from Sesame Street with that sketch about how Elmo gets Christmas every day and eventually he gets bored of Christmas… you need the bad stuff to put the good things in perspective. I mean, not cancer. Cancer’s bad. You don’t need that sort of perspective. But it is nice to have the downside to remind us of how incredibly lucky we are.

MIKE MILLS: Michael sings about elements a lot. Air, fire, water.

MICHAEL STIPE: Reveal was our summer record. Again, I think it’s very strong. Songs like “I’ll Take The Rain”, that’s the winter song, the only one. I felt that the record needed something to balance all that sunniness. The other one might be “Disappear”, which is very sun-drenched, maybe because I was in Tel Aviv when I wrote it. Yet even then it has a creeping darkness.

18 STRANGE CURRENCIES

From the 1994 album Monster. Released: April 1995.

Chart positions: UK No 9, US No 47

Proceeding at the swaying pace of “Everybody Hurts”, “Strange Currencies” is nonetheless a more disturbing and far less wholesome proposition. As with most of the album, Stipe was taking the opportunity to explore the themes of infatuation taken to unhealthy, probably illegal extremes: “I’m going to make whatever it takes/Ring you up, call you down…” This has all the trappings of a ballad, yet it’s coated with a film of sleaze and desperation.

MIKE MILLS: Yeah. “Strange Currencies” – I love that sort of thing if it works. Peter was tired of playing acoustic guitar. So we decided to play electric. And it got a bit of a bad rap because between Out Of Time and Automatic For The People we got a boatload of new fans who expected us to continue to make the same sort of record, but we never do that anyway – long-time fans know that, but the short-term ones didn’t.

PETER BUCK: The songs were all kind of third-person. It’s a perverse record generally – all the songs are about peeping and stalkers.

MICHAEL STIPE: For me, Monster was a sonic experiment. I really wanted to experiment with my voice and different textures and push the really grainy, bassy, ugly sounds as far as we could. And yeah, the lyrics match that. They’re kind of gross and disgusting! But it was obvious that I was role-playing.

17 NIGHTSWIMMING

From the 1992 album Automatic For The People. Released: July 1993.

Chart position: UK No 27

This ballad, which initially did not look like it was going to make the final version of Automatic For The People, is cut from the finest REM cloth, with its wistful orchestration, gently clashing themes of pleasure and melancholy, distantly recalling the innocent skinny-dipping frolics in which the band indulged in their earliest days at a lake near Athens, Georgia. It’s recalled with the distance and regretfulness of age (Stipe was in his thirties by now) and, once put through his lyrical filter, emerges as a vague but effective remembrance of things past.

PETER BUCK: Michael says that song is autobiographical, and I certainly remember that after shows back in Athens in 1980, just when the band started out, we’d all pile into cars and go off swimming naked – it’s something you can do in rural areas. But it wasn’t necessarily such an idyllic time and some people back in Athens didn’t end up leading such idyllic lives. It made sense for the record – it was the first song we finished for the album

16 HOW THE WEST WAS WON AND WHERE IT GOT US

From the 1996 album New Adventures In Hi-Fi. Released: April 1997.

Chart position: none

A bold, even perverse choice of single, “How The West Was Won And Where It Got Us” was evidence of REM dabbling in a less four-square, more amorphous rock sound, with its avant-jazz piano break and spindly synth accompaniment. It was also evidence of their precipitous commercial decline – and perhaps their indifference to same. As the music delineates a vast, Monument Valley-style landscape, Stipe adopts the manners of a wandering balladeer, telling “the story of my life in trying times” in a series of typically oblique and elusive images. It was one of the last recordings made for New Adventures In Hi-Fi.

PETER BUCK: New Adventures… was generally an exercise in trying to write songs on the fly – it really conveys the feeling of what it’s like to be at the eye of the hurricane. You get the vinyl copy of that album and it makes more sense, with the double gatefold sleeve and the array of Michael’s photos.

MIKE MILLS: That was a fun song. I don’t believe it did anything as a single. We were in the studio in Seattle, it was one of the last things Bill [Berry] did with us. He was sitting there, tapping something away at the drums and I was sitting there at the piano saying, “Yeah, that’s cool,” and I struck up with something and, literally, that song took as long to compose as it does to play. It just fell right into place, it was amazing.

15 ALL THE WAY TO RENO (YOU’RE GONNA BE A STAR)

From the 2001 album Reveal. Released: July 2001.

Chart position: UK No 24

With its rattlesnake rhythms and strangely un-REM musical colouring and glazed finish, “All The Way To Reno” could be seen as the wry musings of a band making their way back from the Sodom and Gomorrah of celebrity and high fame, contemplating a starry-eyed young wannabe skipping along the yellow brick road in the other direction. The song is full of ironic acid-drops, but kindly in its restraint towards the object of its attentions – she’ll soon find out what stardom is all about.

MIKE MILLS: Yeah, the idea of that song is that you already are a star. You can be as famous as you want to be, but that doesn’t necessarily make you a star.

MICHAEL STIPE: And the twist is, Reno, Nevada – I’m not dissing Reno, it is what it is, but it’s such a backward destination. The thought of being so backwater that Reno is the big city to them! We get it in Athens, people come in from the county of a weekend and Athens, Georgia is a big night out for them.

14 WHAT’S THE FREQUENCY, KENNETH?

From the 1994 album Monster. Released: September 1994.

Chart positions: UK No 9, US No 21

Largely composed by Mike Mills, “What’s The Frequency, Kenneth?” takes its titular cue from a bizarre incident in which US news anchorman Dan Rather, while out walking on Park Avenue, was chased by a stranger who, as he rained blows on him, kept repeating the phrase: “Kenneth, what’s the frequency?” The attacker was thought to be one William Tager, who actually murdered a TV stagehand and was imprisoned in 1994. Believing the media to be beaming messages into his head, and believing Rather to be called Kenneth, he was supposedly demanding of him the frequency being used to transmit the waves. Stipe and co use this as a springboard, an almost inappropriately upbeat rocker, tidal in its exuberance and matched by a video in which Stipe and Mills in particular came on as almost studiously extrovert. All this is cover, however, for a digressive and introverted lyric at odds with its musical setting.

MIKE MILLS: It is an exuberant song but it’s actually complex, even musically. It’s quite deceptive, the way the chords go round – it sounds very smooth, sounds like it’s going the way it should go, very free-flowing, but if you were to break it down, figure out the chord structure, you’d realise there’s a lot of changing back and forth that you don’t necessarily hear when you’re listening to the song.

MICHAEL STIPE: The “Kenneth” thing, that’s just one line of the song. It happens to be a great title! We ended up singing that song with Dan Rather on David Letterman’s show. He has a great sense of humour, very self-deprecating. Also, he lets you see the guy behind the anchorman. He shows you he’s just an actor – well, not an actor, just a guy doing his job. He’s not a world expert, just a conduit between you and the news, or somebody’s idea of the news. But he had a glint in his eye and I liked that.

PETER BUCK: “Withdrawal in disgust is not the same as apathy” – that, for me, is the big lyrical moment in that song. The title is kind of a catchword. But that line is where the heart of that song is.

13 POP SONG 89

From the 1988 album Green. Released: May 1989.

Chart position: US No 86

With a sizeable advance from Warners in their pockets, REM became all too aware of their status as almost-famous and of the expectations on them to haul themselves into the limelight. This they undertook with an element of caution, self-consciousness and playful irony that didn’t always sit well. “Pop Song 89”, however, which quotes heavily from The Doors’ “Hello I Love You”, subverted its own breeziness with a lyric that prefigures the dilemma-wracked “Losing My Religion”(“Should we talk about the weather?/Should we talk about the government?”) and an extraordinary video in which Stipe dances with three topless girls. Strangely, this disconcerted rather than thrilled US audiences – and the single was not a commercial success.

PETER BUCK: We actually wrote that in 1987 for our 1987 tour. I said to Michael, “Why are you calling it that?” And he said, “I don’t know, it’s a pop song, it’ll probably come out in 1989, so let’s call it ‘…89’.”

MIKE MILLS: The song itself is really not quite as ironic as the title. But it was good that we did two versions of the video. There’s one in which there are black bars across Michael and the girls’ chests as they’re dancing, and one without the black bars. MTV America would only play the one without the black bars.

MICHAEL STIPE: There was total satire in the videos. I had big hair like a lion and I knew I was going to shave it off – but I wanted to do that shimmy-shake thing with a bunch of girls, but have everyone be topless, break down that whole sexist thing. So I found three women who were cool, “Yeah, I’ll show my tits on TV, why not?” We were big, but not yet huge in 1989. Aside from London, in Europe we were sharing a bill with Gene Pitney, playing small venues of well under a thousand people. There were places we weren’t that popular then, there are places we’re not that popular right now, America being one of them!

12 DAYSLEEPER

From the 1998 album Up. Released: October 1998.

Chart positions: UK No 6, US No 57

REM, and Stipe in particular, are compulsive changelings and especially so on their 1998 album Up – their first without Bill Berry. They struggled to bring on a musical metamorphosis, just as they were struggling to come to terms with the new imbalance of working as a threesome. Up is a fascinating, if incomplete exercise for REM, with its retro-futurist instrumental adornments and efforts to weave an Eno-esque ambient mist. “Daysleeper”, however, its ‘dream sequence’-style mid-section apart, indicates that, whatever new postures or approaches they choose to adopt, their work is haunted by recurrent themes. The see-saw musical action of the song and its lyric, which apparently concerns an office worker whose consciousness patterns are ravaged by the conditions of his work, struck a familiar chord with both REM fans (British ones particularly) and a relieved record company alike.

MIKE MILLS: Up was a very difficult album. We were trying to redefine ourselves and find out what the dynamic was between the three of us – every rule you’ve ever had about how to make a record has gone out the window. There were a lot of things going on at once. But I’m very proud of that record. It takes a while to listen to it, but I think if you give it enough time it rewards you very well. I like to think, anyway.

MICHAEL STIPE: Up is too long, we could have hacked a couple of songs off as B-sides, some of the performances are a little tentative, but the material’s strong.

MIKE MILLS: “Daysleeper” was the record company’s choice, they were the ones who picked it – I guess they couldn’t think of anything else. Sure, it’s the one that sounds most like REM, but picking a single that sounds exactly like the band, I’m not so sure that’s the way you should go about it. I think maybe you should pick something because it’s a great song, whether it sounds like the band or not. These days, when it comes to singles, we let the record company pick what they want – after all, they’re the ones that are going to have to do the work on it.

11 GET UP

From the 1988 album Green. Released: September 1989.

Chart positions: none

Although Stipe returns here to his familiar theme of dreams (“Dreams they complicate my life/Dreams they complement my life”), the song is actually addressed to the notoriously deaf-to-the-alarm-clock Mike Mills. Fiercely poppy and upbeat, it again sees REM and Stipe caught both pop-wise and politically between the attractions/imperatives of languishing on the margins or engaging directly with the pop mainstream. It’s as if they’re slapping themselves, trying to instil a new alertness into their act which is at odds with their natural, romantic tendencies. It reflects the push and pull of a band determined to be themselves, maintain their identity and integrity, yet reach out to a wider audience.

MIKE MILLS: Apparently, it’s about me. I wasn’t aware of this until the 1999 tour, when Michael told me and several thousand other people in an arena, onstage.

MICHAEL STIPE: Yeah, we’d written all these heavy, big songs and we wanted to do something that was a bit more bubblegum, you know, Orange Juice and The Monkees and The Banana Splits. So we did things like that and “Pop Song 89”.

PETER BUCK: Songs like “Get Up” are kind of big, dumb pop songs and that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. “Louie Louie” has probably got to be the best rockin’ song ever, and it’s dumb! It’s really dumb, it’s badly performed, and nothing’s beat it as far as I’m concerned.

10 E-BOW THE LETTER

From the 1996 album New Adventures In Hi-Fi. Released: August 1996.

Chart positions: UK No 4, US No 49

Shot through with the device of the title, “E-Bow The Letter” is another of REM’s unapologetic anti-single singles, heavy-duty avant-folk-rock that concedes nothing to radio sensibilities. Stipe’s intense, garrulous lyric, based on an unsent letter to an unknown second party, is underscored by a guest vocal from Patti Smith. Whatever is vexing them is inscrutable to the casual listener; indeed, obscurely compelling as the song is, it seems from one angle like a deliberate attempt to shed extraneous fans. While “E-Bow…” rewards the devout and persistent REM fan, it went over relatively poorly in the US. Strangely, however, in Britain, it would prove their biggest-selling single to date.

PETER BUCK: An ‘e-bow’ is a little magnet that vibrates the strings and gives off this rather mournful, oboe-ish sound. Robert Fripp used it a lot. It was a totally unhip device during the punk era, which is kind of why I got into it.

MIKE MILLS: We first met Patti Smith in 1995. We’d asked her to sing on a previous record, but her husband, Fred, who was still alive at the time, was very protective of her, he wouldn’t allow her to work and I’m not sure she wanted to. So then, a few years later, she was thinking about stepping out again and we asked her to come sing – she actually joined us for “Dancing Barefoot” at the World Theater in Chicago. And not long after that she agreed to perform on “E-Bow The Letter”.

MICHAEL STIPE: We did have an ability to release the most unlikely songs just to push radio as far as we could push them, get more good music on the radio. And there was… for a while. “E-Bow The Letter” sounded the death knell for us being able to do that! But I think it represents some of my best writing.

9 BAD DAY

From the 2003 album The Best Of REM. Released: October 2003.

[eventual chart position: UK no 8]

“Bad Day” doesn’t so much nestle as bristle alongside the greatest hits package from which it’s taken. Not unlike Wire’s recent return to the direct ferocity of their Pink Flag days. “Bad Day” derives its energy from the band’s collective anger at the appalling misadventures of George W Bush and his neo-con goons, particularly since 9/11.

MIKE MILLS: Certainly, “Bad Day” is an angry song and we are certainly angry at our government. But the problem is also the acquiescence of the American press. It’s their job to question the government and they’re just blithely going along with whatever George W Bush says. It’s appalling. America is very definitely tilting to the right in a very bad way.

MICHAEL STIPE: The songs we ended up choosing for the best-of were much louder, much harder and in-your-face songs. It’s not easy to be an American right now. I’m not claiming myself as one of the so-called experts on the 24-hour news channels, but from an emotional point of view, I would say that the country is going through… you know, we really are a young country and because we’re so fucking powerful, people forget we’ve only been around for a couple of hundred years. We are like teenagers, we’re brash, we’re loud, we’re opinionated, we’re kind of brilliant but really dumb at the same time and this country has never experienced the kind of loss of innocence that the attack on September 11 brought about on that scale. It would have been a tragedy for it to have happened anywhere in the world, but for it to happen in the US… I have to say, it’s an entire nation that has been cosseted, myopic, geographically so separated – that’s how we’re brought up. Unless you’re very rich and have great schooling, this is the geography that’s instilled in you. Mexico doesn’t exist – it’s this big brown puddle below Texas. Canada is this big, grey hinterland above Detroit. We’re not taught about the world. The percentage of Americans who hold passports is shocking. And discounting Pearl Harbor, this was effectively the first time we’d been attacked in our own land. I personally believe that with our current administration, there’s a degree of betrayal that’s going on in terms of why things are happening around the world, why certain things are happening at home. They’re using this whole emotional thing, but they’re not answering any of the questions, like why this happened. It’s not digging below the surface, it’s simply taking the anger, frustration, fear, and converting it to a certain agenda.

PETER BUCK: Certainly, with “Bad Day”, it’s the first chance we’ve had to have our say about what’s going on in the world right now. It’s about the way that the media is over everyone’s shoulder to such a degree that no-one makes choices any more, they just get told what to do. It’s like, hey, this is what’s patriotic this year, you have to agree with it. Well – I don’t agree with it. It blows my mind that somehow in present-day America, they’ve twisted it so that if you don’t agree with the ‘president’ who wasn’t actually elected, then you’re not a patriot. What’s more, you’d think that the people who should be supporting US troops should be the government. Yet while those young people are over in Iraq getting killed, the US government has passed a new tax bill which cuts benefits to veterans and schools for military kids. I know if I was over there in 100 degree heat, risking my life to ensure oil fields were safe, I’d feel a little pissed-off that my benefits were disappearing so that multi-millionaires can get a tax break. Which, by the way, I will be happy to get!

8 ELECTROLITE

From the 1996 album New Adventures In Hi-Fi. Released: December 1996.

Chart positions: UK No 29, US no 96

Bedded in some simple but affecting piano work from Mike Mills, “Electrolite” proved to be a minor success for REM, not least perhaps because it felt like their quintessential early work – shades, for instance, of “(Don’t Go Back To) Rockville”. A hoarse Stipe namechecks Jimmy Dean and Martin Sheen as he aerially surveys Hollywood and its icons, but there’s a feeling that he’s receding, leaving the 20th Century: “I’m outta here”, he croaks at the end, lending the song, and the album it concludes, a valedictory feel.

MIKE MILLS: I was surprised at the reception that song got. I knew it did well here on the radio but you never know how these things are going to go over live.

MICHAEL STIPE: With New Adventures…, even as we started the record, Peter said, “This album is going to represent a quieter, darker side of us.” And I said, “You mean like [Springsteen’s] Nebraska?” And he said, “Yes, exactly.” So we were trying to do Nebraska. And he said, those pictures you take out of the car window, that’s what the artwork should be for this record. A year and a half later, that was the landscape that was being used to reference the record.

7 THE GREAT BEYOND

From the 2000 album Man On The Moon. Released: November 1999.

Chart positions: UK No 3, US No 57

A big hit in the UK, “The Great Beyond” sees Stipe take a second whack at the subject matter he’d first explored on the song which inspired Milos Forman’s biopic of the late American comedian Andy Kaufman (on which Stipe was an executive producer). With its huge, galvanising pop hook, it’s a resurgent example of quality REM bisecting with populist REM.

PETER BUCK: I think Michael tried to boil down what Andy was about in that song, rather than mention it by name. I really like that song. I thought it captured something about Andy. It really sticks in the mind.

MICHAEL STIPE: It was great working with Milos Forman, great working with Jim Carrey, Courtney Love – Danny DeVito was such a fucking professional. I admire ambition so much and if it’s ambition that they don’t know where it’s coming from or where it’s headed, take it and use it to create – that’s what you’re here for, create, so fucking do it. Cut the crap. And all those people that I mentioned recognise that. Like all artists, they occasionally fall on their face, they sidestep, they make wrong decisions and have to make them publicly, which ups the stakes – but wow, that was a great experience. It was also important for us as a band to work on something, to do something, without the pressure of an REM album. It was great to score a movie, writing music for someone else, and it put us in a place that enabled us to do Reveal. It was a great sidebar, and doing that really galvanised us as a band and brought us back together. It made us believe – our convictions were, fuck the difficulties, fuck everything, I want to be in this band with you.

6 STAND

From the 1988 album Green. Released: January 1989.

Chart positions: UK No 48, US No 6

With its almost do-si-do/line-dancing-style instructions, and Bill Berry and Mike Mills providing supporting vocal interruptions, “Stand”, like many tracks on Green, is a slightly affected yet effective exercise in musical and lyrical contrivance that works either as a piece of clever silliness or as an existential call to arms, personal or political. It depends how seriously you choose to take it – but it’s a further example of REM’s duality at a time when they weren’t quite sure where they were at in pop’s food chain and were handling their success with kid gloves.

MIKE MILLS: It is a big, dumb pop song and very silly in its way. And yet the message it’s putting out is a very good one. Be aware of who you are, where you are and why you’re there. You can’t get any more universal than that. Think of what you’re doing and why. It’s almost a carpe diem sort of song.

PETER BUCK: I get the feeling that it’s certainly a song about taking control of your life and look where you stand, and stand there and be what you are. Play that song to 10,000 people and it’s something else again – or you could play it at a party and dance to it. We’d been on the road in 1987, and we’d certainly played big places in America. And with that and having a new record label, a newish producer, there was this thought, ‘Hey, let’s really put those drums up there.’ I could remix that whole album and create a much warmer record. With Green, we did stop doing things completely intuitively and started to think about what we were doing.

MICHAEL STIPE: It’s a wake-up call – I think I felt the need for that at the time. Politically, and whatever.

5 MAN ON THE MOON

From the 1992 album Automatic For The People. Released: November 1992.

Chart positions: UK No 18, US No 30

Although Andy Kaufman tragically died of cancer several years before the track was released, “Man On The Moon”, with its rangy slide guitars and epic simplicity, exudes some of the warmest, fondest, most uplifting feelings of any REM track. Sublimely nostalgic, it’s as if Kaufman isn’t so much being lamented as reborn through the song – which, in effect, he was, since he’s gained a posthumous reputation to rival that which he enjoyed during his eventful life, spent baiting TV audiences with his conceptual pranks and wrestling women.

MICHAEL STIPE: I wouldn’t let him go, man. I’d never had the intention of bringing him back to the degree that I did by writing that song. I didn’t even know the song was going to happen like it did. He was absolutely original. I don’t think I’d want to sit at a dinner table with the guy, but from a distance… he was doing on TV what I was talking about wanting to do on radio. He was just blowing the doors wide open.

MIKE MILLS: Andy’s reputation is two-dimensional at best, especially in Britain, where if he’s known at all it’s as Latka in Taxi. But in America, he was unpopular. He wasn’t really a comedian, he was a performance artist who occasionally did funny things. He was an agitator, a provocateur. He loved to mystify and enrage. He was on Saturday Night Live, where he came out and did routines like Mighty Mouse. But eventually he became so unpopular that the show eventually ran a vote, probably at Andy’s instigation, asking people to choose whether Andy should ever come back again. And they voted “No”.

PETER BUCK: He was someone we all really loved. And because he was so generally loved among musicians as a whole, it took me a while to realise just how out of step he was with the world. He never stopped pushing it forward, to the point where you genuinely wondered if he was actually insane or schizophrenic, he was that far beyond the norm of what you were supposed to do. Here’s an idea – a comedian who doesn’t make you laugh. All right, there are quite a few of those when you think about it, but here’s a comedian who’s not actually trying to make you laugh, who’s setting out to make you feel totally uncomfortable.

4 RADIO SONG

From the 1991 album Out Of Time. Released: November 1991.

Chart position: UK No 28

Featuring a contribution from hip hopper KRS-One, the significance and unprecedented nature of this rap/rock crossover, the fourth single and opener from Out Of Time, was overlooked at the time, especially in Britain, where a great many rock groups were rather hastily discovering a ‘dance element’ to their music. But this was no wholesale effort from REM to transform their image to keep pace with changing fashion, rather a one-off, demonstrating an untapped capacity to chop out funky riffs with the best of them. KRS-One’s guest rap underscores the theme of the song as explored by Stipe, a more measured variation on Morrissey’s “hang the DJ” rant.

PETER BUCK: It’s funny, when we came to the UK to do press, everyone said, “Oh, it’s totally baggy.” And I had no clue what baggy meant. I thought it was an insult, you know, the way an old man’s baggy, or something.

MICHAEL STIPE: I like that song. A couple of years ago, I did a hip hop track, which has yet to be released – I come in on the background vocals. The guy who produced it is a great friend of mine. And he told me something which had never occurred to me, which was that we were the first white band to bring someone from hip hop into our music. And I was like, “Hang on a second – what about Run-DMC and Aerosmith?” and he said, “No, that was Run-DMC covering ‘Walk This Way’ and bringing Aerosmith in. And not only that, but you went to the Godfather, you went to KRS-One, the guy who wrote the book.”

PETER BUCK: I don’t think people noticed what we’d done in getting KRS-One in. That’s partly because radio stations wouldn’t play it because it had rapping on it. And, first of all, it’s not actually rapping, it’s toasting. Second, it’s not that big a part of the song, it’s just the cool part. I thought it was a cool thing to do, a way of saying, hey, we’re all in this together.

MIKE MILLS: Could we do a follow-up to that? It could happen. But it would have to be natural and feel right. You don’t want it to look forced or like you’re trying to be trendy. But the fact that we’ve done it 12 years ago kind of makes it OK. We couldn’t be accused of jumping on a bandwagon, since we did it so long ago.

MICHAEL STIPE: You go back to about 1968 – there was a wild moment when the radio was completely run by squares and straights who were so out of touch they had no idea what was going on, so they just hired people to tell them, say, Jim Morrison was a good singer. But that changed at the end of the ’60s and radio has completely sucked ever since in America. Even in Britain it’s limited, but tastes are much broader and people are not afraid to mix it up.

3 EVERYBODY HURTS

From the 1992 album Automatic For The People. Released: April 1993.

Chart positions: UK No 7, US No 29

Deservedly, REM’s most widely known song, and one which has enjoyed a long afterlife. Its message, as encapsulated in the title, is uncharacteristically plain, direct and unadorned by allusiveness or stream of consciousness. Its transparency is its virtue, borne along respectfully by a musical arrangement that is stadium-rock-friendly yet free of bombast, histrionics or cheap crescendos. It took on a wider significance in the mid-’90s, as Kurt Cobain’s suicide and the disappearance of Manic Street Preachers’ Richey Edwards raised awareness of a mood of implacable nihilism and despair among many young people, even during the political fair weather and relative prosperity of those times. Briefly, the ‘cult of despair’ was all over the media, but even after it supposedly abated, “Everybody Hurts” went on to become a universal anthem of consolation in what sometimes seems like a happy, hedonistic and heartless world. Stipe, who in person often strikes people as shy, eccentric, remote, disconnected, is here responsible for one of rock’s great moments of empathy and connection with a mass audience.

MIKE MILLS: Michael certainly has a good feel for what has to be written, but I don’t buy into that too much – looking back, there was an element of coincidence – it’s not as if we could have foretold what was going to happen to, say, Kurt Cobain. Retrospectively, it did chime in with the times, but I don’t necessarily feel that reflects any great credit on our behalf.

MICHAEL STIPE: “Everybody Hurts” was a nod to “Love Hurts ” [written by the country composer Boudleaux Bryant and covered by The Everly Brothers]. We didn’t really know what we had done. I love that song and I can’t even claim it as my own. I do feel it belongs to the world at this point. It’s a hard song to sing, especially on the bridge – but we’ve been doing it live and I think I’ve found a way of singing it where the audience can sing the high part and I can sing the low part.

PETER BUCK: It is the one that charity appeals always request to use. So people who never listen to rock music will always hear the song, generally in conjunction with – and not to make fun of these things – ferry disasters or earthquake appeals. So it pops up in very un-rock’n’roll places. And we don’t accept payments for that sort of usage. So when I bump into older people on airplanes, when they quiz me, they always know that song and they always know it in the context of some terrible disaster.

MICHAEL STIPE: It took me a long time to figure out that if I’m feeling something, there’s a good chance that I’m not the only person in the world who’s feeling it. And if I’m fearless enough to let that work its way into the songs, my contribution to what we do, then usually I’m dead on. Yeah, they wave mobile phones to it these days. That’s cute. I’ve been on the receiving end of those calls several times!

PETER BUCK: In the mid-’90s, I remember cocaine coming back, totally strong. And that’s certainly the stuff that drives a whole lot of people to despair. And I’m not just talking about fucked-up musicians, I’m talking about it reaching right out into society, into places like Wall Street where they were all doing coke and stuff. I really think it had a big social impact. You do a lot of that stuff and your natural pleasure centres, your endorphins, after a while they shut down. You can never get a ‘real’ happy high any more, you know, from walking in the park or whatever.

2 DRIVE

From the 1992 album Automatic For The People. Released: September 1992.

Chart positions: UK No 11, US No 28

“Drive” is a dirge, certainly, but it’s among rock’s finest. Funereal in pace yet thunderous in impact, it feels like the last raging testament of rock’n’roll before its anger is spent. A pessimistic and downbeat counterpart to tracks like “The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite” and the balm of “Everybody Hurts”, it occurred at a particularly weather-beaten moment, after 12 long years of Republicanism in the US, of being “Bushwhacked”. It also came at a moment when rock music was in its last throes of innovation and dominance, something Stipe senses when he sings, “Maybe you rocked around the clock”. Some 11 years on, it’s become clear that rock music’s ability to reinvent itself and reassert its centrality in people’s lives is all but defunct – meanwhile, here we are again with another Bush in charge and dealing with the burning after-effects of another Iraq war.

PETER BUCK: We definitely wanted that as a first single because it really represented Automatic For The People well, and it certainly wasn’t “Shiny Happy People”. We had put a lot of poppy stuff out on singles, and “Drive” was kind of dark. Nowadays, marketing people tell you that, unless maybe you’re, say, Mariah Carey in her prime, you only get one shot at a single so you’d better go with your best shot. Back then, the idea was to put out something that would get radio play and then you’d follow up with the real hit when the album came out.

MICHAEL STIPE: I was obsessed with the idea of radio as being the only conduit for anyone who was young and an outsider – back at a time when the internet didn’t exist and there weren’t magazines that catered to those needs. And yet radio continued to suck, to be this sucking black hole. Also, there’s a tip of the hat to David Essex there, a homage to one of my favourite songs of all time, “Rock On”.

PETER BUCK: There was a feeling at that time that rock’n’roll, the spirit of adventure, was something you just weren’t seeing. I mean, you had great records, I enjoyed the Nirvana era and even Guns N’ Roses. But I remember thinking, we’re really not going to see rock’n’roll records dominating the charts any more for much longer. In a way, I feel things have come back round to the way they were in the ’50s when on the old Ed Sullivan Show you’d have The Rolling Stones and The Beatles on it, but then you’d have a troupe of Hungarian gymnasts. Literally. And a guy spinning plates. I thought rock’n’roll was going to kill that whole concept of loveable entertainment, it was going to be about saying what you mean, mean what you say – but loveable entertainment is totally back. Dance steps, choreography schools, getting your teeth capped, get a weave if your hair’s going, smile all the time. There’s a place for that, but I always hoped that rock’n’roll would push entertainment into a different area, that it’d be more about a shared sense of meaning in your life. But no, it’s all back.

1 LOSING MY RELIGION

From the 1991 album Out Of Time.

Released: February 1991. Chart positions: UK No 19, US No 4

REM’s music has always been marinated in irony and here was the supreme example. Following Green’s several attempts at ostensibly big, dumb, self-consciously pop songs, the single that finally pushed them way over the top commercially wasn’t a ‘please-buy-me’ capitulation to mass sensibilities but one of their most ‘natural’ and personal testimonies, the mandolin and melody running as clear and as beautiful as spring water. There’s none of the forced extroversion that occasionally characterised REM at this time – rather, it sees Stipe agonising over the pressures and compromises of fame, the potential loss of integrity and privacy. “I don’t know if I can do it,” he declares, tottering along the fine line that has always defined REM: “I’ve said too much/I haven’t said enough.” Yet rather than REM putting on make-up and seeking out the commercial spotlight, for “Losing My Religion” it was the spotlight that sought out REM in their own dark, quiet corner, doing their own thing. And the world fell in love with them for it. That, and Stipe’s silly dance. Perfection.

PETER BUCK: I bought the mandolin at the end of 1989 and I wrote the song, the music, in about 1990, so I hadn’t been playing it that long and didn’t play very well – I still can’t really. I only pick it up to play “Losing My Religion”.

MIKE MILLS: The record company were using it as a warm-up to “Shiny Happy People”. They didn’t expect it to be a hit.

MICHAEL STIPE: “The One I Love” was the song that had established us on radio. So, after that, we consciously put out singles prior to the album that would totally challenge radio. The idea was, let’s blow the gates wide open, knowing that radio would play whatever we did and whatever the record company threw at them, because they had six weeks before the album. So we had this clout to release these incredibly strange songs that they’d then play on the radio, which in our minds would open up radio, open up formatting, would make it available to the Grant Lee Buffalos of the world. We were being altruistic but a little cocky as well. I mean, “Losing My Religion”? There’s no chorus, there’s no guitar, it’s five minutes long, it’s a fucking mandolin song. What kind of pop song is that?

MIKE MILLS: Musically, it’s very straightforward, but there’s something satisfying about that song, in the sense of the way the sound of the mandolin combines with the chords, the appealing, evocative nature of the lyrics – and a fabulous video. I have to admit, I’m not really a great fan of videos, but there’s something about the video for that song which made its success. And you put that together and it’s kind of a fluke, but thank goodness. I’m not even sure if that song could be a single now, if it would even be selected. But it came out at the right time, the right place…

MICHAEL STIPE: They said I stole the dance for the video to “Losing My Religion” from David Byrne in “Once In A Lifetime”. But that’s not true. I actually stole it from Sinéad O’Connor. The director of that video had a very clear idea of what it was going to be. My performance took a lot from Bollywood, Russian constructivist posters and so forth – he wore his references very clearly and openly. He wanted my performance to be complete Bollywood, where I’m sitting facing the camera like Cleopatra on the fainting couch, with my legs wrapped around each other and flowers all around me and then turning in this contorted way and delivering my line. And he worked about half a day with me doing all these poses. Then after half a day he came up to me and said, “I feel really uncomfortable.” And he went to the bathroom and vomited his guts out. Then he came back and said, “I don’t know what to do.” He had this budget, all these actors, this very expensive set and it wasn’t working. I was giving everything that I had but it wasn’t working. So I said, “Turn on the camera and let me do what I do, let me sing my lines the way I would sing them.” And I didn’t have a mic stand – so I had to do something with my hands. And I thought of “The Last Day Of Our Acquaintance” by Sinéad O’Connor – and her performance in that video was fucking beautiful. So I did my version of Sinéad. And it worked.

PETER BUCK: For Out Of Time, we’d decided to turn our back on touring, even though we assumed it was going to kill our career stone dead. We had a big meeting, in which we considered if we were going to have to cut our salaries, collect on insurance for not touring. And following the success of “Losing My Religion”, the album sold 10 million copies. So we were like, “Whatever.” But I was quite prepared for it to go the other way. My feeling was that if we can’t be successful being who we are then I just don’t want to be successful. There’s nothing worse as a fan than when you see a band with a unique identity who will then give it up just to have a hit. Because what are you giving it up for? Money? Well, hey, I have a middle-class attitude towards money, I assume I can always work or something. But to sell your soul – or sell your soul and then not sell records – think about how bad that would be. And I know people that’s happened to and now, they’re like, “What was I thinking?”

The post REM’s 20 greatest singles of their major-label era appeared first on UNCUT.