The Drive-By Truckers that went into Chase Park Transduction studios in Athens, Georgia in 2002 to record Decoration Day were, in a couple of important respects, a different band to the one who had made its predecessor, 2001’s Southern Rock Opera, an astonishing double concept album somehow assembled on a shoestring.

The Drive-By Truckers that went into Chase Park Transduction studios in Athens, Georgia in 2002 to record Decoration Day were, in a couple of important respects, a different band to the one who had made its predecessor, 2001’s Southern Rock Opera, an astonishing double concept album somehow assembled on a shoestring.

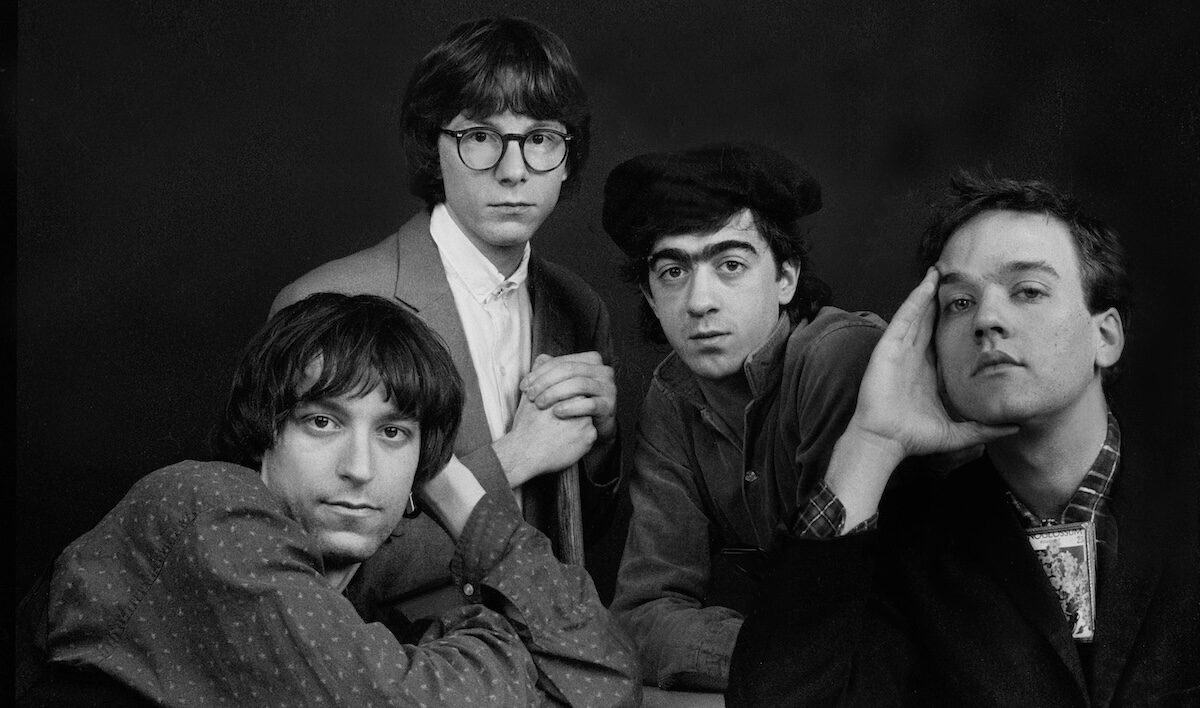

Most obviously, there had been a rearrangement of personnel, not the Truckers’ first or last. Guitarist and occasional songwriter Rob Malone had left, replaced by a 22-year-old kid from north Alabama called Jason Isbell. Along with this promising addition, Drive-By Truckers had acquired a couple of other things at least as significant. For the first time in the almost two decades that founders Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley had been playing together, they had (some) money, and a reasonable expectation of an audience. Southern Rock Opera had been a minor hit. It turned out that there was, after all, a market for an old-school Southern rock band with a new kind of idea of the South, as a place both less and somehow more romantic than previous apologists or detractors had presented. “The duality of the Southern thing”, they called it.

Importantly for the album that Decoration Day would become, however, this modest success had been bought at considerable cost. It is exhausting even to read Drive-By Truckers’ touring itineraries of the early 2000s. One chunk of October 2002, to cite a more or less random but pretty typical fraction of this self-inflicted punishment, included 12 shows in 14 nights in eight states. Enduring this had left all concerned somewhat frazzled, and in Hood and Cooley’s cases, wondering whether this was really any way for men nearing 40 to be living. On the guilelessly titled “Hell No, I Ain’t Happy”, a piledriving rocker that would have fit well amid the rowdy furies of Southern Rock Opera, Hood roars from the back of the van, “Eighty cities down, eight hundred to go/Six crammed in, we ain’t never alone/Never homesick, ain’t got no home”.

But this was something else that had changed between writing Decoration Day and recording it. For Hood and Cooley, going places now also involved leaving people. If the album has one emblematic line, it is Cooley’s “And ‘Lord knows, I can’t change’/Sounds better in the song than it does with hell to pay”: it’s one thing to exult in Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird” when you’re young, another trying to live it as middle age looms. Decoration Day becomes a long grapple with maturity, burdened by the fear that its composers might have got what they wanted too late to be able to keep it. “The drifter”, laments Cooley elsewhere in “Sounds Better In The Song”, “holds on to his youth like it was money in the bank”.

Southern Rock Opera had been, in terms of its sound, very much a clue-in-the-title record. On Decoration Day, Drive-By Truckers draw on a much broader range of Americana, as they had on formative albums Gangstabilly and Pizza Deliverance. Hood re-embraces orthodox country on “My Sweet Annette” and punkish alt.country on “The Deeper In” – the latter an anguished and compassionate telling of the woeful true story of a pair of biological siblings imprisoned in 1997 for consensual incest, but not before they had produced four children.

He goes raucous, revved-up rockabilly on “Sink Hole”, conveying a struggling farmer’s fantasies of interring a foreclosing banker in the titular abyss. Cooley’s contributions include the escalating, menacing choogle “When The Pin Hits The Shell”, an elegy delivered with a snarl, decorated with a keyboard solo by Spooner Oldham, and the exquisite acoustic closing ballad “Loaded Gun In The Closet”, a study of a couple held together by mutual appreciation of each other’s desperation; marriage as a Mexican stand-off. It’s a grimly appropriate finale, and also about the most optimistic contemplation of domesticity on the album.

Hood’s other contributions include the self-explanatory “(Something’s Got To) Give Pretty Soon” and “Your Daddy Hates Me”. The former is a Replacements-like mid-tempo affair, caught between shuffle and swagger, in which Hood despondently diagnoses the cause (“Living hard to chase the dream/Way beyond our ways and means ”) and the effects (“You say you just want compromise/Then act different all the time”). The latter is a malevolent, almost Sabbath-esque plod, as if the heavy metal records beloved by the teenage Hood have become the only appropriate backdrop for his middle-aged wretchedness (“You always knew I was a screw-up/Long before I screwed us up”).

On Cooley’s exuberant boogie “Marry Me” – a title that in context sounds more like a dare than a proposal – he nails the couplet that summarises their predicament: “ Rock’n’roll means well/But it can’t help telling young boys lies”. Jason Isbell, at this early stage of his life, had not yet learnt these and other things the hard way, though he had recently married Shonna Tucker, who plays upright bass on “Sounds Better In The Song” and would formally join Drive-By Truckers shortly afterwards (their eventual divorce would inspire a good few songs itself).

He writes of what he does know, which at this point is his family, their home and the lore of both. The album’s title track is Isbell’s inhabitation of a foggily remembered real-life feud between the Hill and Lawson clans of Alabama. Though Isbell is descended from the Hills, he sings from the perspective of a Lawson maintaining a grudge which has long since superseded the original grievance: people who are angry without being entirely sure why are a recurring theme in the DBT canon.

“Outfit” still seems unlikely to be dislodged from the top five songs Isbell will ever write. The bonus live album included with this reissue, a largely acoustic set recorded in Athens in June 2002, features the first-ever performance of the song; already, the audience whoop at several of the better lines. “Outfit” channels Isbell’s own father, whose story Isbell tells with Springstonian economy. His narrator and/or dad reflects that “I used to go out in a Mustang, a 302 Mach 1 in green/Me and your Mama made you in the back, and I sold it to buy her a ring”. You know the guy instantly: he loved his freedom, and he misses the car that furnished it, but when one thing led to another he knew what his responsibilities were, and he doesn’t want his boy to make basic mistakes of his own.

“Don’t call what you’re wearing an outfit” is good advice; “Don’t let ’em take who you are, and don’t try to be who you ain’t” is better. When Isbell introduces “Outfit” on stage now, he sometimes notes that it’s a favourite of people who either have a great relationship with their father – as he appears to – or a terrible one.

Patterson Hood has always insisted that Decoration Day is, in its way, as much of a concept album as Southern Rock Opera, and he would know. It’s an album about choices and consequences, and whether we really get much say in either. It was also the second Drive-By Truckers album of which someone could reasonably wonder: is this the greatest rock’n’roll record of the 21st century? They’ve made at least another half-dozen contenders for that title since.

The post Reviewed: Drive-By Truckers – The Definitive Decoration Day appeared first on UNCUT.