From Uncut Take 332 [December 2024], The Cure’s Robert Smith on their first new album for 16 years, Songs Of A Lost World, love, loss and ageing, the Moon landings, abandoned projects, War And Peace, nearly splitting up, The Cure’s 50th anniversary and ambitious plans for another two new Cure albums…

From Uncut Take 332 [December 2024], The Cure’s Robert Smith on their first new album for 16 years, Songs Of A Lost World, love, loss and ageing, the Moon landings, abandoned projects, War And Peace, nearly splitting up, The Cure’s 50th anniversary and ambitious plans for another two new Cure albums…

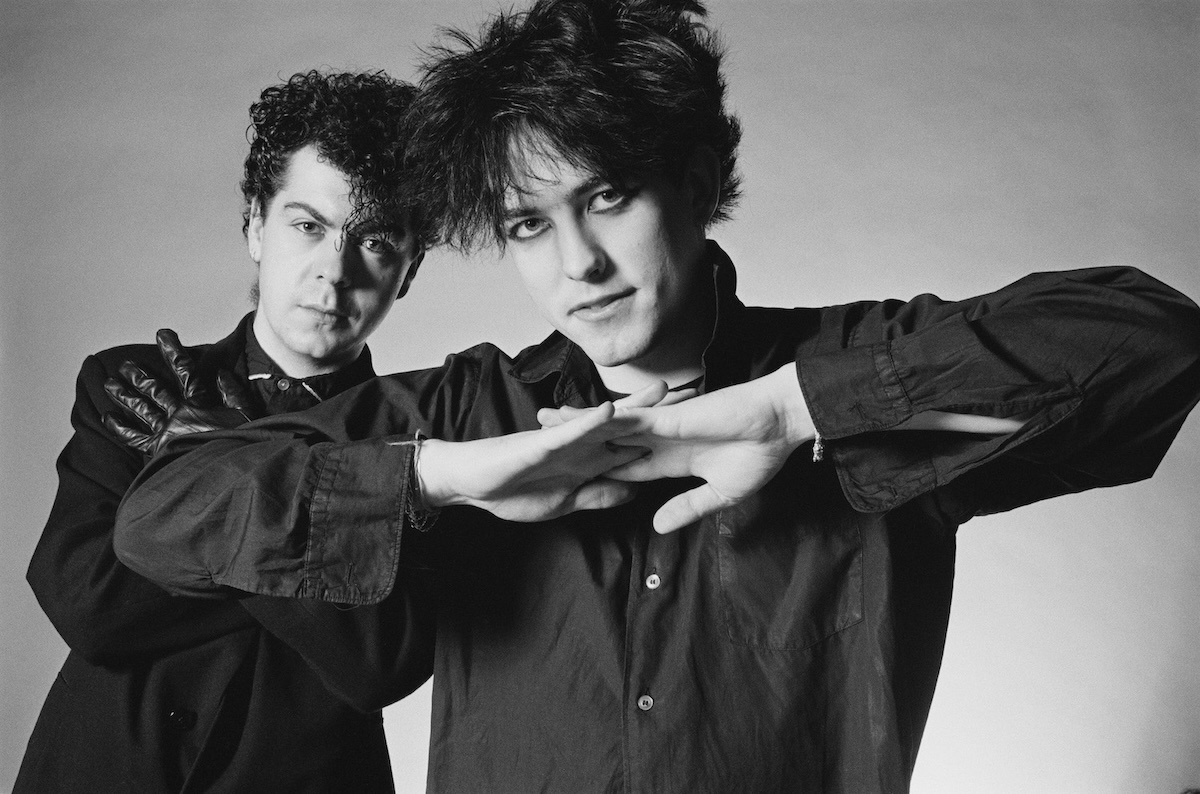

A rare and revealing new interview

September 12, 2024 and Robert Smith is at Abbey Road Studios. Smith has spent time here recently, listening to the Atmos mix of Songs Of A Lost World – the first new Cure album for 16 years. Today, however, Smith can be found in Studio 3, where in a rare and revealing new interview he will dig deep not just into this new album, but also the past and future of one of British rock’s most enduring and fascinating musical institutions.

The interview forms part of a small amount of promotional activity to support the album: The Cure will also play two shows at the BBC Radio Theatre on October 29, to be broadcast two days later on Radio 2 and Radio 6 Music, and another concert where the band will perform Songs Of A Lost World in full. Opting for a less-is-more strategy, Smith has clearly decided to let this new music speak for itself.

As it transpires, Songs Of A Lost World is a deeply personal record, full of heartfelt songs about love, loss and ageing, that is as dramatic and emotional as the best music from The Cure’s imperial phase. There are songs that address knotty philosophical questions, others that take umbrage with the invasive nature of the modern world and even one that is inspired by the Apollo 11 Moon landing. These inquisitive qualities underscore the depth and breadth of Smith’s creative vision, yet two songs on the new album hit closer to home: on “And Nothing Is Forever” Smith reconciles a promise he broke to

a dying friend, while “I Can Never Say Goodbye” is about the unexpected death of Smith’s older brother, Richard.

This new album has undergone a lengthy gestation

“Even though most of the songs are very personal, they’re not exclusive, they’re not things that only happened to me,” Smith explains.

Although it has been such a long time since The Cure’s last album 4:13 Dream, Smith has hardly been a recluse. During that time, he oversaw the final reissues from The Cure’s back catalogue, collaborated with artists as diverse as Gorillaz, Chvrches, Deftones and Noel Gallagher, became patron of Heart Research UK and even found time to curate the lineup for the Meltdown festival. But while The Cure have played over 250 concerts in the years since the release of 4:13 Dream, these mammoth, three-hour live sets have felt like extended celebrations of a singular legacy – until last year, that is, when Smith began to incorporate into their setlists new material destined for Songs Of A Lost World.

As we discover, this new album has undergone a lengthy gestation. In 2017, he envisaged an album that was explicitly linked to The Cure’s 40th anniversary the following year. But things never quite worked out as Smith intended. At one point, as The Cure approached their 40th anniversary, Smith even contemplated calling time on the band he’d formed as a 19-year-old in Crawley, West Sussex. But fortunately, wisdom prevailed.

Songs Of A Lost World is thematically cohesive and richly atmospheric

Instead, in 2019, Smith began working on a separate batch of songs that eventually yielded Songs Of A Lost World. As with The Cure’s best work, Songs Of A Lost World is thematically cohesive and richly atmospheric – a monumental and immersive experience on a par with their 1989 masterpiece Disintegration, where Smith wrestles with regret, loss, confusion and anxiety as friends, family and a world he once knew slip away from him.

“Some Cure albums have been put together in a certain way,” Smith explains. “Disintegration, Pornography or Bloodflowers have an atmosphere. Other Cure albums like Kiss Me… or Wild Mood Swings are much more scattergun. I like them, but I’m engaged more with the albums that have got an emotional core. I wanted this to be one of those albums.”

When did you officially start writing this album?

When the band first started out and we were doing the traditional route of album, tour, album, tour, writing an album was just what we did. But I don’t think there was really an official beginning to this album, it’s been drifting in and out of my life for an awful long time. If I have one regret, it’s that I wish I hadn’t said anything about it in 2019, because we had only just started it. For various reasons, things happened and the idea got pushed back. But there have been definite points along the way where I’ve thought, ‘Ah…’

“Life came crashing down on me”

Key in the history of the band is if I know what the opening and closing songs are, the album is halfway done. So I can remember those two moments and I can remember thinking, ‘We’re definitely going to make a new album.’ But honestly, in probably 2016, 2017, I was preparing for the 40th anniversary of the band and I thought a new album would be the way to do that. But life came crashing down on me and it never got done. As things turned out, it was probably good that I didn’t do it, because the songs that we were going to record in 2017 are not the songs we ended up recording in 2019.

How come?

We had the 40th anniversary of the band in 2018 and the 40th anniversary of the first album in 2019, so I thought we should sum up the band and where we’d got to. It was a grand plan, and grand plans generally don’t work very well in my experience, so it wasn’t really being done for the right reasons. It was a bit triumphal, I suppose, and the tone of it was wrong. As it turned out, what happened in 2018 was a great way to mark the anniversary of the band and it also allowed me the time to think about why we would make a new album. What then happened in 2019 was much more natural. There was no longer this idea that we were celebrating something or marking something. Everything evolved out of that. It became much more artistic, rather than: ‘Here’s The Cure after 40 years – be amazed!’

So the songs were all written over that period? There were no older songs?

Five of them have been written since 2017. But one’s 2010, one is 2011 and one’s about 2013 or ’14. There’s so many songs to choose from. We recorded 25, 26 songs, I think, in 2019. We recorded three albums in 2019! I’ve been trying to get three albums completed because my idea was that after waiting this long, let’s just throw out Cure albums every few months! With hindsight, you think, ‘Really?’ But it will work out this time because having finished this one, the second one is virtually finished as well. The third one is a bit more difficult because… Yeah, if we get that far…

“It’s slightly bewildering, if I’m honest”

Are there a whole spate of demos that get worked on simultaneously or specific songs that get finished before you move to the next one? How does it work?

In the first 15 years of the band, the writing was pretty much all me. I conducted everyone. I showed the band what they should play, everyone interpreted it and then I’d say no or yes… less often yes! Simon [Gallup] would often join in. There’s always a great Simon song on the early albums – sometimes more than one, to be honest. In the latter half of the band’s career, I’ve said to the others, “If you’ve got something, play it to me. And if I like it we’ll do it.” Often, some of the weird stuff isn’t me at all – like the jazz songs on Wild Mood Swings. It forces me to write lyrically in a different way and the band becomes better for it. If it was entirely left down to me, I think we would be a much less interesting band. So the process has opened up over the years. But by 2019, I had a group of songs that I had written over the previous 10 years and I thought ,‘This is what I want to focus on.’ So in 2019 all the songs we recorded were my demos, which hasn’t happened for a very long time. There is a cohesion to the songs, which is the thing I most wanted about the album. But it’s been a strange and protracted process because from recording in 2019, here we are five years later and the first album is finally coming out. It’s slightly bewildering, if I’m honest.

You played five new songs that have made it on to this new album while on tour in 2022/23. Did playing them live shape them?

We’ve done that a few times. Particularly in the early days, when we’d be writing songs as a band, I’d have a couple of beers and go out on stage and sing whatever came into my head. I used to record everything out front and I’d listen back and think, ‘That’s a really good line!’ Songs from Seventeen Seconds and Faith were written like that. But with these songs, we’d already recorded them, I’d already sung them, so we knew what we were doing. Three of them, I thought, ‘I won’t get any better than that,’ because the vocals were very raw, they were written and sung in a genuine emotional state. But singing these songs night after night and gauging the audience’s reaction, I could see how far I could push it, emotionally, vocally. We were playing them a lot better than when we recorded them. So we replayed everything with Simon and then I spent a few more days with Reeves [Gabrels]. If he’s got people in front of him, Reeves plays in a totally differently way than in the studio, he’s much more expansive, so capturing that was important. As it turned out, after the European leg of the tour, I redid all the vocals at home. Then when we came to mix the album, I preferred the original vocals. Even though I felt like I was singing them better, whatever that means, after the tour, they didn’t have that something that the original vocals had.

“I streamlined the whole thing”

As a side point, when The Cure played the Royal Festival Hall in 2018, you performed two songs, “It Can Never Be The Same” and “Step Into The Light, that haven’t made the new record. I presume they’re going to be finding their home?

They were quite old then. We recorded them originally for the 4:13 Dream album in 2007, 2008. We have since rerecorded those and a couple of others from that session and some others from The Cure session before that, and a song from the Wish album sessions in ’91. So, yeah, I haven’t been afraid of going back in and using stuff that didn’t seem to work at the time. There are songs that have been left behind that have a great melody or a good chord progression, but I haven’t managed to understand what the song is, I haven’t been able to write lyrics for it or I haven’t been able to sing it, or it’s just in the wrong tempo. Something about it just doesn’t work, or it doesn’t fit with the other songs. So we rerecorded quite a few things – there’s a big pool of songs. I imagined Songs Of A Lost World was going to be relentlessly downbeat. A few people who listened to it said, “The songs individually are really good, but it’s too much. You can’t expect people to listen to this much doom and gloom. You need something else in there.” So a couple of the songs were knocked off and a couple of songs brought in. I streamlined the whole thing. It was originally 13 songs. Now it’s eight and it is a much better record for it, because it has a bit of light and dark.

Was there a track that unlocked the record for you?

I was struggling to find the right imagery for the opening song, “Alone”. Then I rediscovered a poem called “Dregs” by Ernest Dowson, which inspired the line “every song we sing, we sing alone”. Ultimately, we are alone. I wrote “Endsong” in one night. The album sessions were called Live From The Moon, because it was the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11, the lunar landings. I was outside one night and I remembered back to when I was 10 years old, standing in the back garden with my dad looking up at the Moon and I thought, ‘Here I am, still stargazing.’ I was born in 1959 and I grew up in the glorious 30 years from the end of the Second World War where it felt like the world was getting incrementally better every year. The world was on an upward trajectory and the Moon landing was part of that. Around the time I turned 16 in ’75, it seemed like the world stalled and it has been travelling down ever since. That’s the beating heart of the album, the songs of a lost world. All that is the Lost World. This is how I feel about the young me: ‘Where did it go?’ At that moment I thought, ‘Well that’s the end song. I’ve got the opening song…’ Those two moments both happened in 2019, which is probably why I started blathering about a new album to people, when in fact we had 26 pieces of music and two songs. I was being slightly disingenuous, but I did it in good faith. I thought it might motivate me: when you make a promise in public, it becomes more difficult to break it. As it turns out, I finally got there. But it’s just taken a lot longer for various reasons.

“I was relieved when it came to an end”

How did lockdown impact on the record?

I feel I could have utilised lockdown, I could have finished everything. Pretty much over a two-year period, very little went on. I was in a very privileged position where I’ve got enough room at home. After a while, I relished certain aspects of lockdown. I loved the fact there were no planes in the sky. The birds were singing a lot more. Everything was reverting back, it felt like an old world. I’ve never had a smartphone. There’s only one thing in the house that connects to the internet and if the lid’s shut, the house is disconnected. There’s a part of me that enjoys solitude. I read 100-plus books in the first year of lockdown. I read all of John Le Carré’s books in one go. Stuff like that. I never thought I’d have time to do any of these things. I read War And Peace! I listened to vast amounts of music. It was almost like an extended holiday. Meanwhile, all my remaining aunts and uncles died in care homes. My cousins, everyone I knew, was dealing with this awful reality of not being able to go and engage with their own families. My mum and dad had already died, so I didn’t have to go through that. On a personal level, it was a very selfish lockdown. But I grew tired of it. I was relieved when it came to an end.

Songs Of A Lost World deals with some dark themes. You’ve talked about experiencing loss during the creation of the record. How was it, capturing that?

Our songs have always had a fear of mortality, I suppose, for want of a better way of putting it. I’ve wrestled with it since I was eight years old. But as you get older, it becomes more real. Death and dying becomes more and more part of the every day, unfortunately. When you’re younger, even without knowing it, you romanticise it. Then it starts happening to your immediate family and friends and suddenly it’s different. “I Can Never Say Goodbye” was about my brother dying. I tried to achieve the right balance between the outpouring that I had after the event and putting it into the song. Some of the versions I did were overwrought. Doing that song live, sometimes it would break me up and so it was very difficult to not go over the top. That was true for me writing the words to all the new songs, trying to have the right tone. I don’t feel my age at all, but I’m aware that I turned 65 this year. So I want to reflect where I am, and that the things that matter to me now aren’t the things that mattered to me 20 years ago. I wanted the songs to mean something. Whereas there have been big periods of The Cure’s history where some of the songs mattered and some of them didn’t. On this album, they all matter.

“I’ve had a different outlook to everything since”

How did this record change you?

The change had already happened to me, I think. I pinned so much on 2018 as an anniversary year – once it was gone I thought every moment from this point on is pretty much a bonus. I thought that the Hyde Park show would be it, I thought that was the end of The Cure. I didn’t plan it, but I had a sneaky feeling that this was going to be it. But it was such a great day and such a great response, I enjoyed it so much and we got a flood of offers to headline every major European festival. “Do you want to play Glastonbury?” So I thought maybe it’s not the right time to stop. I wasn’t stopping because I didn’t want to do it any more, I just thought it would allow me a few years when I’d still be able to do something else. I wasn’t that bothered, funnily enough. I’d arranged everything to end in 2018, so when we got to 2019, I felt relieved. “We did it!” I’ve had a different outlook to everything since. Pretty much everyone that died that meant something to me died prior to 2019, so I felt like I’ve got to make the most of it.

The freedom of splitting up, but then not actually having to split up?

Yeah. 2019 was the culmination of all that. We had a fantastic year playing festivals. Then, because I started to work on the songs and we needed to expand the band to do justice to them live, Perry [Bamonte] came back. Since then, it’s like another version of The Cure has gone out and played. When we next play, it will become something else again. There’s this sense of us changing, but very slowly, all the time. I look forward to it. It’s a blessing because I’ve found it very hard to live in the moment. I think that’s another thing about lockdown I enjoyed. I found myself spending the day not thinking about anything to do with tomorrow. It was very unusual for me, because I’m normally always thinking ahead. I’ve fallen back into that way of thinking, unfortunately. I haven’t managed to retain that sense of just existing in this moment, not yesterday and not tomorrow, but now.

How did it feel when you’d finally finished the album?

That was here in Abbey Road. They did the Atmos mix here over a couple of days and that was the very last part of it. After that, you can’t really change anything. I was sitting here on my own and listening back to it and that was the moment I thought, ‘It’s done!’ It was a mixture of enormous relief at having actually finished it but also I really like it! I’m glad that I was flexible enough to change my original ideas of what it was going to be midstream and to turn it into a much more engaging piece of work. It’s about 50 minutes long and you end up somewhere different than where you started out.

“There was an enormous freedom and great joy”

When can we next expect to see The Cure on stage?

We’ll be playing an album show this year. We were going to play festivals next year, but a couple of weeks ago I decided that we wouldn’t be going to play anything next summer. The next time we go out on stage will be autumn next year. But then we’ll probably be playing quite regularly through until the next anniversary – the 2028 anniversary – which is looming on the horizon. I’m 70 in 2029 and that’s the 50th anniversary of the first Cure album. That’s really it, if I make it that far. So in the intervening time, I’d like us to play concerts as part of the overall plan. The last 10 years of playing shows have been the best 10 years of being in the band. It pisses all over the other 30-odd years! There was an enormous freedom and great joy in just going out and playing music.

Over the past decade, you’ve mentioned a number of different projects. There’s 4:14 Scream, ‘Live In Paris’, the South America tour documentary… Are any of these things going to happen?

They all stalled for different reasons. Most of them will get completed. The South American tour film, we took Tim Pope with us. It was utter chaos. Some of the footage is really funny and the shows were good, but I started watching it all back and thought, ‘Why would we make a film about this?’ We finished the film we made in Paris, but that was probably the worst, the most acrimonious disintegration of any versions of The Cure. It just needed tweaking and finishing off, but I couldn’t be bothered. Then we moved on and I’ve never really come back to it, which is a shame because I suppose time has softened my anger. The Tim Pope documentary will happen. That’s an ongoing thing. It’s the preliminary stuff – all the digitising. Once we do it, it will be done really quick. It’s my perspective on everything that I’ve done with the band. So I’ve been hanging fire while everyone else makes their version of events public. If I do get to the 50th anniversary, that will be the summing up of everything I’ve done with my life, I suppose.

“All those things matter so much more”

What songs inform you as a writer or as a musician?

I first heard Nick Drake’s “Time Has Told Me” on an Island sampler called Nice Enough To Eat. That song stuck with me all my life. His voice, the way he plays, the simplicity of what he does – yet it’s incredibly difficult, impossible to replicate it. And beautiful words. The way he delivers them, it’s all very heartfelt, very emotional. It connects. Jimi Hendrix informs everything I’ve ever done, just because I always wanted to be him when I was a kid. I didn’t know anything about him. I didn’t know he was black. I didn’t know he was American. I didn’t really know he was a guitarist. There was a poster on my brother’s wall of Jimi Hendrix, I thought, ‘I’d like to be Jimi Hendrix. That would be really good fun.’ I mean, I was in school being told what to wear, so being Jimi Hendrix was a great option. Janis Ian’s “Tea And Sympathy” – that has the mood and emotion I tried to capture on this album. Or Joan Armatrading, “Love And Affection”. I’m going back to old stuff, this is my lost world! Bowie obviously always informs everything: ‘Would David do that?’ “Life On Mars” had a huge impact on me. There’s a certain period of everyone’s life, around 13 up to 17, when you discover your own music and books for yourself. All those things matter so much more than they should then. I’m lucky that the things I liked when I was young, musically, I still like.

What’s the best thing about being Robert Smith?

I have led a very privileged life. I can’t believe how lucky I’ve been. I suppose the fact that I’m still upright is the best thing about me because there have been points in my life where I honestly didn’t think I’d hit 30 or 40 or 50. I’m much more relaxed than I used to be. I’m much, much easier to get on with than I used to be. I know I am because people smile at me a lot more than they used to! I’m lucky enough to be able to do something which I always wanted to do – and I’m still able to do it. That’s probably the best thing about being me. I’m still doing what I’ve always wanted to do.

“I always hear that voice, ‘Remember that feeling…’”

That 19-year-old boy in The Cure. Is he still here?

That voice never leaves me. It’s the yardstick that I still use. I remember buying tickets to see Bowie and schlepping up to London. I didn’t have any money and he played for 42 minutes or something. I was like, “Noooo!” I was right at the back of Earls Court. It took me five fucking hours to get to the seat and he finished and there was no encore! So part of me was like, ‘Don’t do that.’ Even though he was my hero, I thought, ‘Come on. If you knew how all these people idolise you, that’s not enough.’ That’s maybe why we play too long a lot of the time. But I always hear that voice, ‘Remember that feeling…’ So the decisions that I make are still informed by this pretty naive 19-year-old voice, which I think is a good thing. I would hate to feel like I wasn’t able to justify myself to my 19-year-old self.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

The post The Cure’s Robert Smith interviewed: “Our songs have always had a fear of mortality” appeared first on UNCUT.