The brand new issue of Uncut – in shops now or available to order online by clicking here – celebrates the era-defining impact of The Stone Roses’ breakthrough. In this expanded extract from our cover story, Mike Joyce of The Smiths recalls being bowled over by an early warehouse party show – as well as highlighting the unique qualities that Mani brought to the band.

The brand new issue of Uncut – in shops now or available to order online by clicking here – celebrates the era-defining impact of The Stone Roses’ breakthrough. In this expanded extract from our cover story, Mike Joyce of The Smiths recalls being bowled over by an early warehouse party show – as well as highlighting the unique qualities that Mani brought to the band.

I saw them play in [July] ’85, under the arches on Fairfield Street, by Piccadilly. They called it a warehouse party – it was just a room with a PA in, and they were selling cans of Red Stripe for 50p or whatever it was. I remember ‘Stone Roses’ being written on the Town Hall and around the Square, and there was a big hoo-ha about that. But otherwise I didn’t really know anything about them.

The first thing I noticed was the drummer, as obviously I would do, and I just thought, ‘Fuck, he’s good. He’s very good.’ As the set went on, Ian was being very aggressive with the crowd and I thought, ‘Wow, he’s fucking cool – a great frontperson.’ The whole thing sounded very different from anything I’d heard before. They were quite punky then, or punkier. It happens every now and again, whether it’s Nirvana or Arctic Monkeys or whoever, you know they’re gonna be massive, even when they’re in the very early stages – there’s something that just makes you go, ‘Oooh’. And that’s what they did. Doesn’t happen very often, but when you do see it, there’s no denying it. I didn’t know any of the material, I was just blown away by what I was hearing, by what I was seeing.

Did they take anything from The Smiths? In terms of musical style, I don’t think so. I could be wrong, but nothing obvious. You might say that John’s guitar-playing on Waterfall is not a million miles away from Johnny, his kind of picking style. And Mani wasn’t a million miles away from Rourkey in terms of style: super-funky, but without slapping bass. But I’d have thought that they would have been [inspired by us] in the same way that when I saw Buzzcocks for the first time, I was like, ‘My god, that’s what I want to do.’ Because they were Manchester lads, and it opens up the door. It’s not middle-class, art-school students from London. So that influence would have been there in terms of, ‘We can do it too.’

Reni was very musical, and you can tell that he’s feeling it, rather than trying to make something fit. He’s loose as fuck because he he plays behind the beat all the time, but he’s not sloppy. He’s just got that loose, relaxed feel, which gives it a swagger. He’s really a lovely drummer to watch, because it’s like gymnastics sitting down. I do like drummers that really go for it, but Reni made it look as though he was just counting from one to 10 – effortless.

Ian’s never been known as one of the best singers in the world, but when you’ve got a drummer who can sing like that, it certainly helps. I’ve only ever sung once on stage, when I was playing with PiL at Reading Festival. There’s a bit in “Cruel” where the bass player Allan Dias goes “Cruel cruel cruel cruel” across the beat, and he said, “Can you do it, Mike? My throat’s fucked.” Of course there was no soundcheck, because it’s a festival. And when we got there, I couldn’t sing across the beat. I couldn’t do it! Allan Dias burst out laughing and said, ‘Don’t sing in the next verse!’ When there’s already four limbs all playing independently, and then you add a vocal on top of that, it takes some doing. So Reni’s a very talented lad.

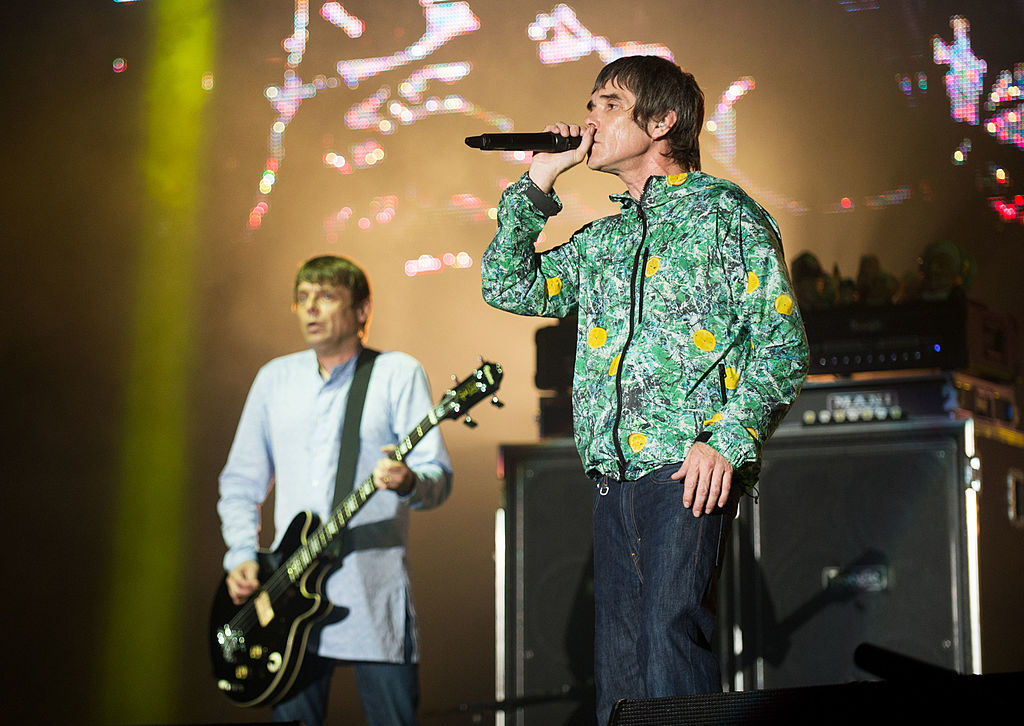

With Mani, it felt like he was the frontman. I’m not too sure how much Ian wanted the fame aspect of being in a band. Every single band that’s ever been in existence wants success. But once that starts to come and you can’t control it, you can’t say, ‘That’s enough now.’ Just before The Smiths split up, it got to the point where Morrissey couldn’t really go out in Manchester. We were struggling a little bit with it. But Mani embraced it. I think he normalised that aspect of his life, rather than having four or five bodyguards walking into anywhere. A funny bloke, super-talented obviously, but he removed all that pop star bullshit veneer that some people adopt. He just didn’t allow that to happen, he didn’t allow people to treat him like that. People talk about him being down-to-earth, and that’s exactly what he was: no bullshit, no nonsense, go out there and play, have a good time doing it and enjoy yourself. Off-stage he was very engaging, always approachable, and made everybody feel at ease.

I played with him in 2011. He was doing a Smiths tribute night at Band On The Wall and he asked me to play two or three songs in the encore. I said to him about a soundcheck, just to run through the songs, and he said, ‘Fuckin’ ’ell, don’t you know Smiths songs?!’ He had a very Manc sense of humour, taking the piss a lot. There was always a one-liner or a quip coming out of him. Every time I saw him, he always had a smile on his face. He’s the kind of guy that you’d always want in your band in terms of keeping spirits up, but he’s also a wonderful bass player. There’s a Primal Scream track that Mani played on called “Uptown” from Beautiful Future, and that’s the pocket right there. There’s no flim-flam, it’s just the same thing over and over again, but that’s the bassline, and Mani’s playing is just stupendous. It’s perfect.

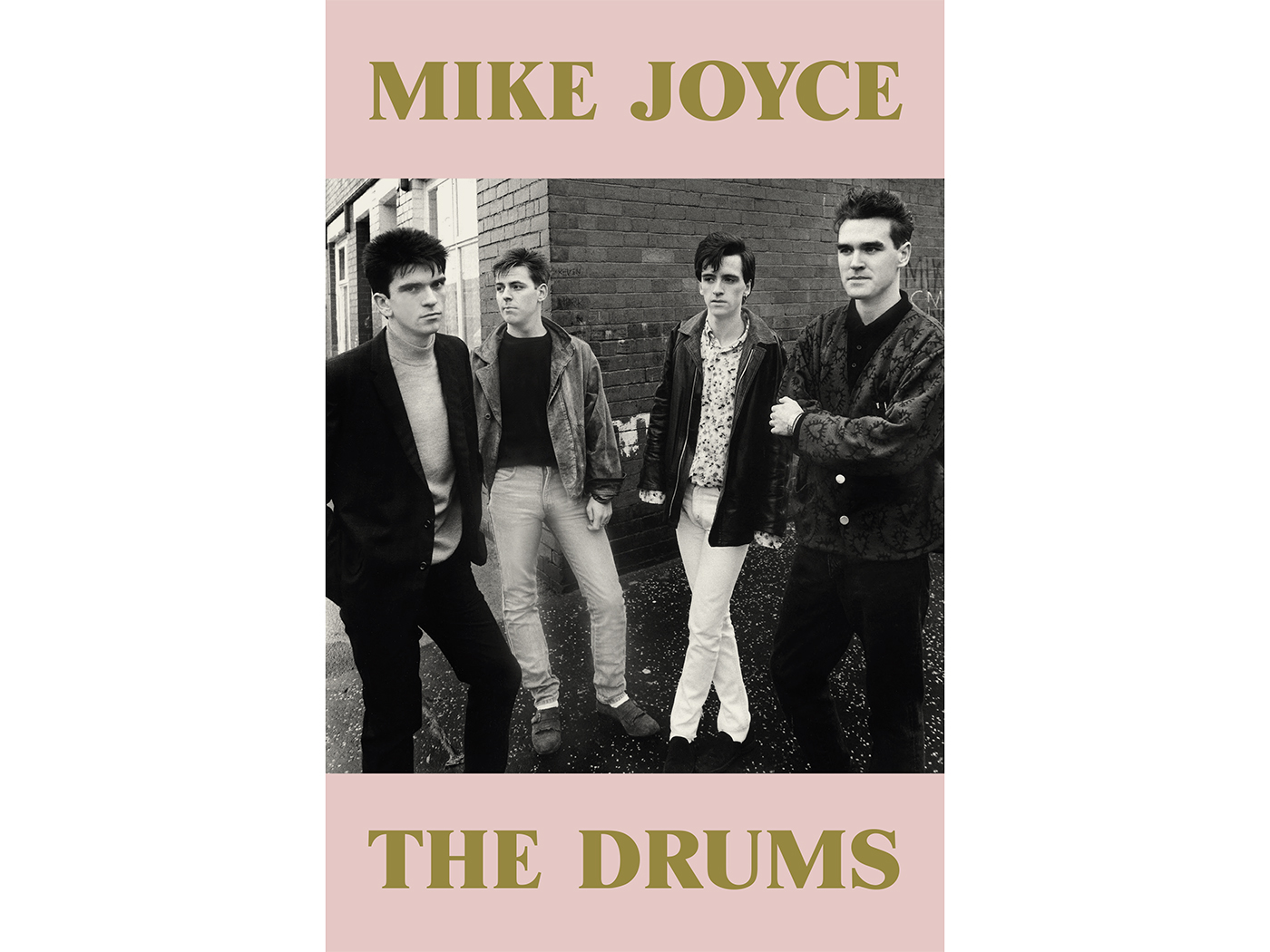

Mike Joyce’s memoir The Drums is out now, published by New Modern

The February 2006 issue of Uncut is on sale now, with The Stone Roses on the cover. Read more and get your copy here!

The post The Smiths’ Mike Joyce on Mani’s pivotal role in The Stone Roses: “No flim-flam – it’s perfect” appeared first on UNCUT.