The making of The Smiths’ Meat Is Murder from Uncut Take 214 [March 2015 issue]…

The making of The Smiths’ Meat Is Murder from Uncut Take 214 [March 2015 issue]…

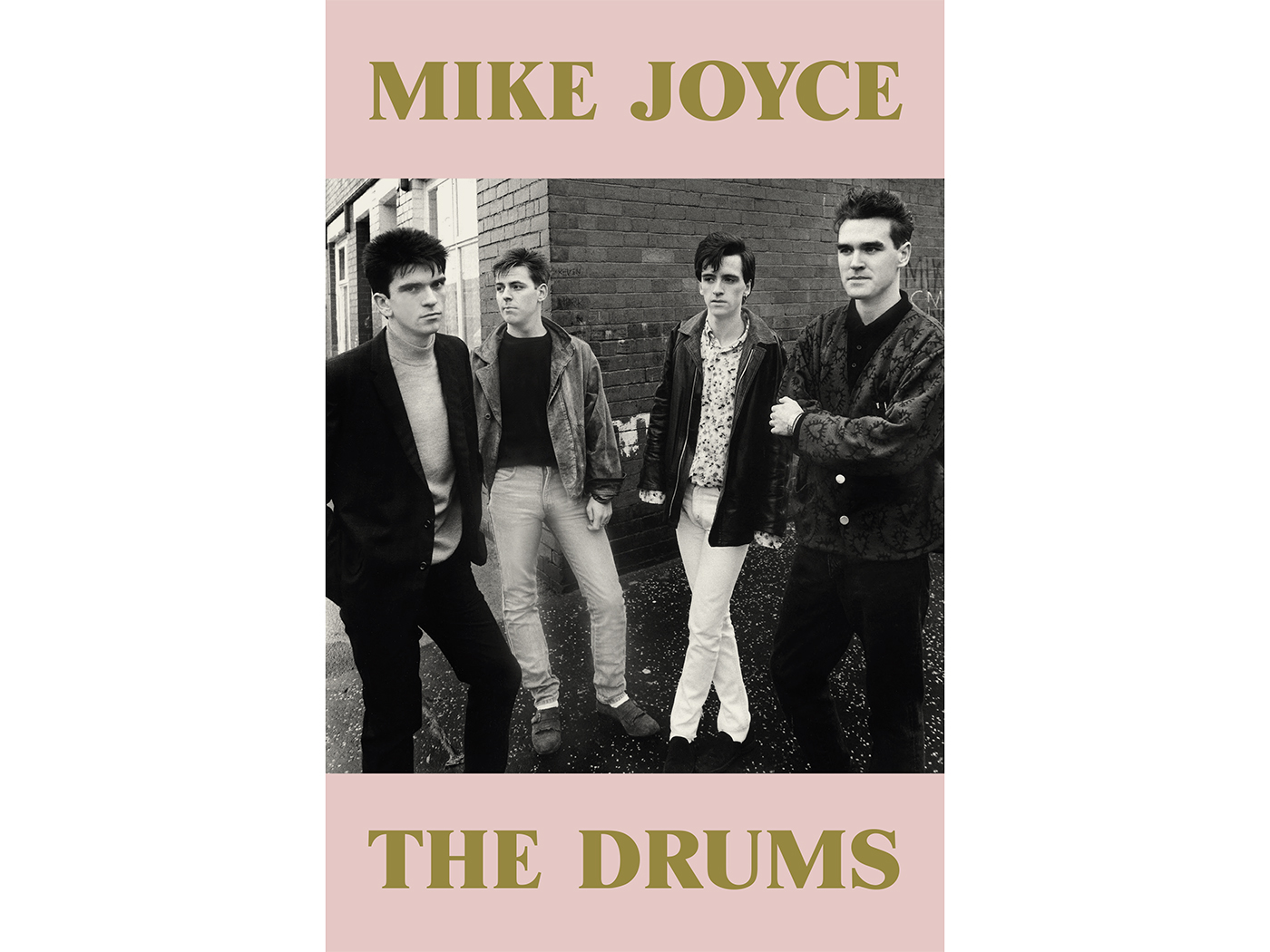

If their first album set out the emotional terrain of THE SMITHS, Meat Is Murder provided a radical manifesto for troubled times, one overshadowed by the “violence, oppression and horror” of Margaret Thatcher. Thirty years on, Uncut tracks down bandmembers, intimate associates, contemporaries (and even Neil Kinnock!) to tell the full story of a band at their closest and most adventurous… A tale of brotherhood, marriage, “live-wire spitfire guitar sounds”, awkward moments in Little Chefs, car races with OMD and the use of sausages as an offensive weapon. “Unruly boys who will not grow up”?

“It was left to us to break some rules and have some fun”

The distance travelled by The Smiths in late 1984 can be measured, to some extent, in car journeys. En route with the rest of The Smiths from their respective homes in Manchester to Amazon Studios in Kirkby during the winter of 1984, Morrissey would sit at the back, to best enjoy the full benefit of the car’s central heating system.

The vehicle – a 1970s white stretch Mercedes rented from R&O Van Hire, Salford – had once been used for weddings. Now it was being used for another type of celebration. The Smiths – along with their fledgling co-producer, Stephen Street – were heading to Amazon to record their second LP, Meat Is Murder. “We had a feeling the grown-ups had left the building and it was left to us to break some rules and have some fun,” Johnny Marr told Uncut.

Despite the weather, the daily trips shuttling to and from Kirkby were conducted in high spirits, characterised by an air of anticipation for what the coming sessions would bring. The interior of the car featured two rows of seats, facing each other like a cab. Morrissey and Johnny Marr would face forward on the back seats, while Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce sat in front of them, facing the rear of the car.

“It was the freezing winter”

If there were any disagreements between the band members, it was usually to do with the heating – which Morrissey would complain wasn’t turned up high enough. “Amazon was on an industrial estate in the middle of nowhere,” says Andy Rourke. “It was the freezing winter. We’d stop for a cup of tea at this mobile café and carry that into the studio. That was our routine for two or three weeks.”

An industrial estate in Kirkby, on the outskirts of Liverpool, in the depths of winter, hardly seems the most auspicious setting from which to storm the citadel. All the same, the work started here by The Smiths on Meat Is Murder was freewheeling and stimulating. “It was very exciting,” acknowledges Stephen Street. “It felt like all the stars were in alignment, everything seemed to be working.”

“They seemed to reflect what was going on in people’s lives”

While historically Morrissey’s songs had lingered on a nostalgic, post-war vision of England – one of juvenile delinquents, underworld spivs and “jumped-up pantry boy”s – Meat Is Murder presented a different, highly politicised side to the band. The songs on the album addressed powerful, contemporary themes including animal rights, domestic and institutionalised violence.

“The Smiths were out there on their own,” Paul Weller tells Uncut. “I thought they were similar to The Jam, really. It wasn’t a party line thing, and the lyrics weren’t always overly political. But they still seemed to reflect what was going on in people’s lives.”

“The issues they were addressing in the songs on Meat Is Murder were socio-political,” adds Billy Bragg. “My politics were more ideological, but The Smiths were more involved in broader issues; we lived in a time when those issues were right to the forefront of debate.”

“The politics of the day had a big effect on the music and Morrissey’s lyrics,” admits Andy Rourke. “That’s what we wrote songs about: our experiences. That comes across in the music, also.”

“Morrissey always wanted to be part of a gang”

If Meat Is Murder helped establish The Smiths as a radical force, it had other, equally far-reaching implications for their career. These were fluid and fast-moving times for the group: since releasing their first single, “Hand In Glove”, in May 1983, their ascent had been rapid and exhilarating, building on a brace of thrilling singles and, in February 1984, a self-titled debut album. Meat Is Murder, though, is best characterised as an exchange of ideas at a higher level.

It moved their story forward credibly, giving them their only No 1 album, in the process dislodging Springsteen’s Born In The USA from the top of the UK album charts. It also represented a point where Morrissey and The Smiths were at their tightest.

“Morrissey always wanted to be part of a gang,” says Richard Boon, then production manager at Rough Trade Records. “He’d never been, because he was such an outsider character.I remember being in the band’s van once when they were coming down to London. They were all wearing white T-shirts because that would make us stand out and they wanted to stand out. By Meat Is Murder, The Smiths had cohered as a gang.”

“It all happened very quickly,” reflects Rourke. “Especially at that time, things picked up even more, and the records started selling better than they had done. I think it always continued upwards, but around Meat Is Murder, it definitely stepped up a gear. They were crazy, busy times.”

“We were in conditions of political and industrial turmoil”

Looking back on the mid-’80s, when he was leader of the Labour Party, Neil Kinnock vividly remembers the social and political landscape of the time. “We were in conditions of political and industrial turmoil,” he begins. “With high unemployment, increases in poverty not seen since the War and whole communities turned into dereliction by changes not only in the wake of the coal strikes but also the steel strike of the early ’80s. The rapid impact of unplanned and unsupported industrial change were evident.”

“There was something in the air in that period, 1984-1985,” agrees Billy Bragg. “It was incredibly intense. You have to see Live Aid in some ways as a reflection of that, because they were all the bands who didn’t want to get their hands dirty with the miners. But as me and The Smiths broke in 1984, we were very much of those times. We weren’t there alone, but in terms of addressing issues, The Smiths were at the forefront.”

“It’s something that I find quite amazing nowadays, how political the ’80s were,” admits New Order’s Stephen Morris, who played a Liverpool City Council benefit with The Smiths. “Greenham Common. Women camping outside, stopping Cruise missiles. That was brilliant. We took things more seriously then. We did loads of benefits, but everybody did benefits. I think maybe it was a continuation of the punk thing, Rock Against Racism.”

“Everyone was political to a degree”

“There were people in the entertainment industry who were very disturbed by what was going on,” continues Kinnock. “When Margaret Thatcher’s premiership turned into ‘Thatcherism’ – in the wake of the Falklands War when the term started to be used – that became a pretty natural focus of antagonism for people who were becoming prominent in pop culture.”

“The Smiths were northerners with a tradition of stubborn working-class opposition, but delivered in a very nice and attractive way,” notes Richard Boon. “It wasn’t standing on the barricades, shouting. It was more subtle. The intent was to reach out to people who felt disenfranchised.”

“Everyone was political to a degree, because everyone was united in their opposition to Thatcher,” says guitarist Ivor Perry, a friend of Morrissey whose band, Easterhouse, supported The Smiths on the Scottish leg of the Meat Is Murder tour.

“Groups like ourselves and The Redskins were far more explicitly political because we were attached to ideologies and programmes of change. But The Smiths were more about lifestyle politics. It was important –but vegetarianism and the school system are not really hard politics, like economics or imperialism, or the subjugation of Ireland or apartheid. Then you had Morrissey’s very strong opposition to Thatcher, as well.”

“We all had to have the same beliefs”

Indeed, Morrissey’s views on Margaret Thatcher were keenly expressed in interviews from the time. “The entire history of Margaret Thatcher is one of violence and oppression and horror,” he told Rolling Stone in June, 1984. “I just pray there is a Sirhan Sirhan [Robert Kennedy’s assassin] somewhere. It’s the only remedy for this country at the moment.” In October 1984 – the same month The Smiths began work on Meat Is Murder at Amazon – the IRA bombed a hotel during the annual Conservative Party conference in Brighton, causing Morrissey to express his “sorrow” to Melody Maker that “Thatcher escaped unscathed”.

“Morrissey was always very outspoken in interviews about Thatcher and the Royal Family,” recalls Andy Rourke. “Did I ever feel uneasy about any of his comments? No, not for my own feelings. I was 18, 19 and I used to panic about what my dad might read. I was OK with it. As a band, we showed a great deal of solidarity and stood behind Morrissey with all his beliefs. We all had to have the same beliefs.”

“The rest of The Smiths were not political,” says Perry. “They liked getting high, smoking weed and drinking. No-one was sat reading political programmes. Morrissey himself was very into feminism and challenging writers. It was radical, but in a way that wasn’t going to affect the average guy on the street, a striking miner or whatever.”

“It was very much the way Morrissey and Johnny felt”

“They were politically idealistic, young, fairly militant people at a time when the country was going through a lot of turmoil,” remembers John Featherstone, The Smiths’ lighting designer. “A lot of bands develop a persona as a band, which is a separate entity from their own individual beliefs. But The Smiths acted the way they did because they were the band and the band was them.

“They were largely self-managed at this time, too. So there was no manager saying, ‘You might not want to say that about the IRA attack on Thatcher.’ As a consequence, the way they acted was the way they felt and the way they talked. Things like Meat Is Murder was very much the way Morrissey and Johnny felt.”

Stephen Street remembers the first time he became aware of The Smiths. “I saw them on Top Of The Pops, performing ‘This Charming Man’,” he says. “I was working at Island as an in-house engineer. There was a session booked for the weekend, so they wanted someone who was prepared to come in. Once I heard it was The Smiths, I said, ‘I’d definitely like to do that.’ You could tell the band were excited. They were very together, they’d done a lot of touring so they were in good shape… really hot.”

“Everything was flying”

Street’s session – in March 1984 for “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now” – marked the start of a long and fruitful relationship with the band. A few months later, Street received a phone call from Rough Trade’s Geoff Travis. “He said the band want to do a record where they want to produce it themselves, and they want to work with an engineer they like and trust – would I be up for it? So we started sessions at Amazon.

“You could tell that the feeling in the band was very positive. They knew they were onto something good. Everything was flying. We would get picked up at 9.30 – 10 o’clock in the morning in Manchester. Get to Amazon at about 11, work through to about eight o’clock at night, perhaps nine, and then get driven back.”

“We were experimenting”

“We figured, why have a producer and have his opinion forced upon us when we can do it perfectly well ourselves?” explains Andy Rourke. “It was a control thing. We really liked Stephen.”

“I was literally the same age as Morrissey,” says Street. “I’m in the same age group as the band. Morrissey was the eldest, then it was me. So it was a bunch of guys together. We were experimenting.”

“I was exploring what I could do,” Johnny Marr told Uncut in 2008. “I suppose I was feeling let loose on that second record. The first period was over – of getting known, learning to play onstage, getting a label and getting a relationship with the audience and then that’s worked out. And then I went into it just rolling my sleeves up and thinking, ‘Let’s see what we can do!’”

“I get the impression that they were pretty well prepared for it – more so than the later albums we made together,” acknowledges Street. “They had a bit of time playing these songs in rehearsals or in soundchecks. ‘Barbarism Begins At Home’ goes back quite a long way.”

“He wouldn’t show them to anybody beforehand”

“We had about 80 per cent of the songs in hand,” remembers Andy Rourke. “We always worked in the same way. Johnny, myself and Mike would put down a rough track with Johnny playing live guitar, just so we had that as a reference. We’d go all the way back and Mike would lay down the drums proper, listening to Johnny’s guitar, and then I’d put the bass on top. Then Johnny would layer all his guitars. Lastly, Morrissey would do his magic over the top.”

For the most part, Rourke reveals, Morrissey would be in the studio with the rest of the band even when he wasn’t specifically required for the recording. “Then he would come into the recording room, with his notebook and his lyrics. He wouldn’t show them to anybody beforehand. That was always an exciting part! You’d hear the lyrics for the first time when he was singing them over the track.”

Writing glowingly of the sessions in Autobiography, Morrissey recalls, “We thrashed through the new songs back to back in order to see – just for the hell of it – where everything would land… Out poured the signature Smiths powerhouse full-tilt.”

Among the songs recorded at Amazon between October and November, 1984, Morrissey described “The Headmaster Ritual” as “a live-wire spitfire guitar sound that takes on all-comers; bass domination instant on ‘Rusholme Ruffians’; weightier drums on ‘I Want The One I Can’t Have’. The Smiths began to stand upright.”

“It was stunning”

Rourke, for his part, describes the sessions as “really fun to record”, while Street professes to have been “blown away when I first heard ‘The Headmaster Ritual’. I thought this was fantastic, and when I heard the lyrics as well, I thought it just sounded so… Morrissey! It was stunning.”

“The Headmaster Ritual”, the album’s opening track, set out the band’s stall. Inspired by Morrissey’s own unhappy schooldays at St Mary’s Secondary, Stretford, the song’s fury was directed at violent beatings dished out by the teachers – “belligerent ghouls” – leaving terrified pupils with “bruises bigger than dinner plates”.

“Barbarism Begins At Home”, meanwhile, addressed domestic mistreatment: “Unruly boys” and “unruly girls”, Morrissey sang, “They must be taken in hand” – a queasy, ambiguous phrase that implied both harsh corrective discipline and also sexual abuse. Morrissey repeats the line “a crack on the head” eight times during the song’s duration, at one point yelping as if in pain himself.

“Rusholme Ruffians”, meanwhile, described stabbings and a potential suicide attempt. The songs they recorded were brimming with violence, but also yearning (“I want the one I can’t have”), romance (“My faith in love is still devout”) and the melodrama of youth (“This is the final stand of all I am”).

“It was all a bit dodgy”

The twice-daily, hour-long commute to and from Amazon Studios along the M62, soon gave way to another journey and a different luxury hire car. After three weeks at Amazon, the band relocated to Ridge Farm, a residential recording studio near Horsham in Surrey. From there, the band’s driver Dave Harper, recalls they would travel to press engagements and meetings in a black limousine.

“It didn’t appear to have a key for the ignition,” Harper notes. “It was all a bit dodgy. You put a large screwdriver, a big one, in the ignition and that’s how you started it. The boot didn’t have a thing to hold it up, so you had to use a broomstick.

“It was originally a funeral cortege car from Holland. Morrissey once asked me about the history of the vehicle. He was sitting behind me. He was in one of his chatty moods. I said, ‘It used to be a funeral cortege car from Holland.’ He said, ‘I wish you hadn’t told me that.’ He didn’t talk to me for the rest of the journey.”

While based at Ridge Farm, the band finished work on Meat Is Murder. Key among that last batch of songs was the title track. “It was me, Mike and Johnny jamming out this very mellow, repetitive riff,” recalls Andy Rourke. “It just happened organically. Morrissey already had the lyrics.”

“I want you to try and create the sound of an abattoir”

“There was no demo,” adds Stephen Street. “The chords are quite strange with that song and they wanted to create an atmosphere. So Johnny sketched out the chords, then we marked it out with a click track, put some piano down, and reversed the first notes to creative this oppressive kind of darkness. Morrissey handed me a BBC Sound Effects album and said, ‘I want you to try and create the sound of an abattoir.’

“So there’s me with a BBC Sound Effects album of cows mooing happily in a field. It was a challenge, but I really enjoyed it. I found some machine noises and put them through a harmoniser and turned the pitch down so they sounded darker and deeper. I did the same things with the cows, to make it sound spooky. It was like a sound collage. The band learnt how to play it live after we’d recorded it.”

“Then I learned the truth”

“The aspirant moment is the title track,” wrote Morrissey in Autobiography. “Each musical notation an image, the subject dropped into the pop arena for the first time, and I relish to the point of tears this chance to give voice to the millions of beings that are butchered every single day.”

Morrissey had become a vegetarian when he was “about 11 or 12 years old,” he told PETA, the animal rights organisation, in 1985. “My mother was a staunch vegetarian as long as I can remember. We were very poor and I thought that meat was a good source of nutrition. Then I learned the truth. I guess you could say I repent for those years now.”

The issues of vegetarianism and animal rights had been thrown into sharp relief a few years earlier with the release of a documentary, The Animals Film. “The matchstick which ignited animal rights in the mainstream in the UK was when Channel 4 aired The Animals Film in November, 1982,” explains Dan Mathews, PETA’s senior vice-president. “There were active groups for decades before, but this film brought the disturbing images to the masses. It connected to the broader political climate, especially to the UK’s class warfare, as animal issues like fur, fox hunting and foie gras were tied to the upper classes.”

“You can’t record an album called Meat Is Murder and slip out for a burger”

“These were the issues around,” adds Billy Bragg. “If you went out of demos, there were always animal rights activists knocking around, no matter what the demo was. It was part and parcel of what the Left addressed at the time.”

Accordingly, if Morrissey was a practicing vegetarian it followed that his fellow bandmates adopt a similar dietary regime. “You can’t record an album called Meat Is Murder and slip out for a burger,” observes Andy Rourke. “After we used Ridge Farm, all our other recordings were done in residential studios. It was great.

“You could fit your own schedule. We used to work, then have lunch, sandwiches, maybe 2pm, then at 6 or 7, it would be dinnertime. You had your own chef there, who’d cook amazing food. We were always thinking with our stomachs.”

While at Ridge Farm, Stephen Street remembers the menu was “meat-free and fish-free. It was a fait accompli. I knew Andy and Mike would give in every now and then. But certainly, when we were together in the studio, no-one ate any meat. Their diet was bloody awful. It was chocolate and crisps. I remember thinking that Johnny looked so slight. No wonder, he hardly ate anything.”

“One time, we stopped at a service station to get some breakfast,” says Andy Rourke. “Everyone ordered scrambled eggs or fried eggs or whatever. I ordered the full English breakfast. When it arrived, Morrissey left the table. Then Johnny left the table. Then Mike left the table. So I was sat on my own with this English breakfast feeling very uncomfortable. I went vegetarian after that.”

“Why have you done that?”

“On one of our many trips, we stopped at a service station with a Little Chef,” adds Dave Harper, like Rourke another fan of the traditional fry-up. “In those days, if you ordered an all-day breakfast it came on a plate decorated with a farmyard scene. So you had the joy of eating bacon and sausages off a plate with pictures of pigs on it. I thought it was quite funny, particularly eating it in front of Morrissey.

“He didn’t make a scene, he just said, ‘Why have you done that?’ I replied, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. Done what?’ He didn’t harangue me, or never forgive me for eating meat. It wasn’t the right environment for him to start sounding off about politics. It never came up. But it was a big thing: what does Morrissey eat? Biscuits, cake, ice cream…”

Shortly before recording began on Meat Is Murder, both Morrissey and Marr had moved back to Manchester after a period living in London. “I used to drop Morrissey off at this big, Gothic, part-timbered Scooby- Doo style nightmare house he’d bought in Hale Barns,” says Harper. “He put his mother in it. It was the type of house an old person would live in; if you went to visit your grandparents and they’d done quite well and they liked having a copper-burnished fire surround and medieval-looking front door with ironmongery studded through it. Johnny was in Hale. He bought the old vicarage.”

“He had his own status to uphold”

Harper would ferry the band up and down the M6, from their homes to engagements in London. “If it was all four of them, Morrissey and Johnny had the seats behind me. Andy and Mike were further back. There was much twisting and turning, chitter chatter, and laughing and playing of cassettes. If it was Morrissey on his own, that was a different kettle of fish. He had his own status to uphold. He’d start at the back, then as the journey went on he got progressively more bored, he’d work his way forwards so he had something to gawp at.”

“It was all a bit chaotic”

During 1984, The Smiths had released three singles as well as two albums – their debut in February, followed by Hatful Of Hollow, a compilation of BBC radio sessions, in November. As 1985 opened, their already prolific output suddenly became complicated. In January – 14 days before Meat Is Murder was released – Rough Trade belatedly reissued former B-side “How Soon Is Now?”, as an A-side single in its own right. The track was later included on the US edition of Meat Is Murder.

“It was all a bit chaotic,” confirms Andy Rourke. “We always felt a little short-changed about their preparation for supply and demand with our records. That obviously affected our chart positions, and so therefore our morale. Geoff [Travis] was doing the best he could for us, maybe it wasn’t just good enough. They just weren’t prepared. Before us, they’d been dealing with quite small indie bands. We were the first mainstream band they’d ever looked after.”

“The Smiths were the goose that was going to lay the golden egg,” says Richard Boon. “The late Scott Piering was plugging away at radio, Mike Hinc, their booking agent, was working really hard. So were the band. Everybody recognised talent and it was a mission to make the public recognise it. But there was tension between the band and the label and they were quick to point out any failings. But the band never accepted any failings of their own.”

“I think we were unmanageable”

The band were also without management at this critical time. “Nobody was steering our boat for us,” confirms Rourke. “While recording Meat Is Murder was great fun, it put a strain on Johnny and Morrissey’s relationship. If anybody had a question about the band that usually would go through management, Johnny would have to take the phone call. It would interfere with the recording process and stress him out; it wasn’t good for Johnny. We definitely needed a manager, but I think we were unmanageable.”

To accompany the release of Meat Is Murder – on February 11, 1985 – The Smiths set out on a 23-date UK tour, which finished at London’s Royal Albert Hall on April 6.

Their tour the previous year in support of their debut album had followed a more typical trajectory of university and polytechnic student unions. But for Meat Is Murder, the band upscaled to theatres, town halls and arts centres. Notwithstanding such live achievements, the album’s only single, “That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore”, peaked at No 49: a further cause of friction with Rough Trade.

The band began the tour travelling to shows in their white Mercedes limo, driven by tour manager Stuart James – who passed away soon after this interview took place. James recalls the band’s strong sense of camaraderie. “They were very tight, but musically, Johnny was the MD,” he says. “Johnny and Morrissey would be talking and suggesting ideas. Then Johnny would present it back to everyone.”

“Aesthetic was really important”

“Both Morrissey and Johnny felt that the aesthetic was really important,” continues John Featherstone. “We spent a lot of time spitballing ideas. Johnny brought up a Stones piece from TV that was lit in a really even flat, very bright white.

“These were the days where you had to go and find a VHS player – so he showed it to Morrissey who said, ‘Maybe we should use that for Meat Is Murder?’ One of the things they liked was very narrow colour palettes. So I lit the whole show through shades of blues and greens, with the exception of ‘Meat Is Murder’. It was such a different song, from a visual standpoint it needed a completely different treatment. So it was lit in just a wash of dripping blood red, to underscore the difference.”

Performed live, “Meat Is Murder” closed the main set on the 1984 tour, positioning the band’s activist agenda at the fore. Backstage, however, Stuart James recalls that there was a slightly more laissez-faire attitude towards maintaining a rigorous vegetarian diet. “Meat was served, but certainly not at our table. Johnny wasn’t interested but Mike and Andy might slip off occasionally for a burger late at night after a gig.”

“For all his faults, Morrissey is often perceived as being dictatorial,” adds Featherstone. “That was never my experience with him. The way this was positioned to the guys was ‘We’re not paying for this; you can spend your money on whatever you want.’ There were many occasions when backstage at gigs, the truck drivers and the bus drivers would pull a barbeque out of the bay of the bus and they’d be cooking up steak and hot dogs, particularly on the US leg of the tour.”

“We lived off lentil stew and rice”

“We used to travel around in a campervan we bought specially for the occasion,” say James’ singer Tim Booth, then a vegetarian, who supported the Smiths on the Meat Is Murder tour. “It was a beautiful old thing from the 1950’s. We lived off lentil stew and rice at those gigs and Morrissey used to come in and eat with us.”

Backstage, the vibes were good. Stuart James remembers Morrissey making the decision to restrict backstage passes to immediate tour personnel only. “We wouldn’t have anyone backstage before shows,” he explains. “I don’t mean just in the dressing room, the whole backstage areas. We’d just have the band and crew laminates.

“They wouldn’t be given out to anyone else, including record company people, who were always wanting to get backstage to talk to the band. But it wasn’t deemed the right place for them, and I’d be happy with that, as well.”

“We didn’t really have pre-show rituals – usually, it was just people dashing to the toilet,” laughs Andy Rourke. “I know Johnny always used to have this superstition that he had to have money in his pocket when he went onstage.”

“Sometimes, he’d completely ignore you”

The dressing room, meanwhile, was by all accounts a relaxed place. “Mike and Andy were court jesters,” describes Featherstone. “You would see Johnny, always with a guitar in his hand, always with a cigarette burning, perched like a pixie at the end of a couch or a coffee table, strumming on a guitar, having four conversations at once.

“Morrissey would be more around the peripheries. He wouldn’t actually be in the room when Johnny was smoking. But if he was, he’d be a little more around the edge, watching what was going on, often reading – a little cone of silence around him. Sometimes, he’d completely ignore you. It took a little while to learn that wasn’t personal, it was just kind of the way that he dealt with stuff.”

Andy Rourke remembers the Meat Is Murder shows as “crazy”, Tim Booth recalls the “intense devotion” of the audiences, while Dave Harper describes the atmosphere as “so hot and exciting, there was sweat down the walls”. Stuart James explains his principal duties during the shows themselves were dissuading enthusiastic audience members from getting onstage. “Later, though, it got to the point where the band wouldn’t think they’d had such a good show if they didn’t have a stage invasion,” he relates.

“You get the lads of terraces,” says Richard Boon. “Both terrace housing and football terraces, embracing the ambiguous character that Morrissey was intent on presenting. The last time I saw Morrissey live was at the Albert Hall when You Are The Quarry came out; it was full of football kids wearing flags and chanting. That started around Meat Is Murder.”

“He used to hide in his hotel”

“Morrissey was a very sensitive human being, and he had this real love/hate relationship with his fame,” observes Tim Booth. “He loved it, he wanted it desperately, but he was also pretty terrified of people and terrified of what came with it. But e was caught between two opposing forces. So he used to hide in his hotel. He wouldn’t go out, he found it overwhelming.”

“Sure, he loved the attention as we became famous,” adds Rourke. “But if fans get too close, we always ended up in situations where Morrissey more often than not was uncomfortable. People were over familiar with him. And bodily contact, people hugging him and kissing him. Onstage, he was fine, but not anywhere else.”

On March 16, The Smiths played Hanley Victoria Hall in Stoke-On-Trent. A few lines into “Meat Is Murder” an object thrown from the crowd struck Morrissey. “It was a dozen sausages with ‘Meat is murder’ written on them,” explains Rourke.

“They’re quite weighty, a pack of sausages, hitting you in the face. That shocked him. Then, when he looked down he saw that it was meat. He was disgusted and he just walked offstage. They were Irish sausages. How do I know? I went to the trouble of wrapping them back up in the plastic. It was like a brick hit him in the face. If they’d unravelled, he may have got strangled by them.”

“Everything got louder than everything else”

“Morrissey loved being onstage, but he didn’t like the boring, mundane, hard work of the travel,” says Dave Harper. “With vegetarians, there’s always the associated illness as they’ve been eating crisps for six weeks. I don’t think it did him a lot of good healthwise, because until you get to another level you’re not getting any decent food – and if you’re a vegetarian, on top of that you’re certainly not getting decent food, because no-one’s catering for you.”

As the Meat Is Murder tour progressed, without a manager and in a period of extraordinary activity, the band responded to the increased pressure in different ways. “Everything got louder than everything else,” says John Featherstone.

“The need to do press and promotion, the need to do shows. It all got too much. Johnny thrives on that stuff to the point of exhaustion. But when Morrissey felt burdened, he would push away. He’d get physically, intellectually and emotionally more distant. He’d cancel interviews and pull back. Johnny and Morrissey both set up professional methodologies that got defined on that tour.”

“It was far too dainty for them”

Many of the people working directly with The Smiths during this period were already close associates of the band. John Featherstone, for instance, had been on board since November, 1983. Rough Trade’s Richard Boon, meanwhile, had first met Morrissey while running Manchester’s New Hormones label: “He sent me a cassette of him singing, saying, ‘I have to whisper because my mum’s next door.’ It had an early version of ‘Reel Around The Fountain’.”

But as tight as this grouping was, it fell to Stuart James to handle the band’s day-to-day duties. “I was their buffer in the middle,” he reveals. “I’d be the person Rough Trade would go to if they wanted to get in contact with the band directly. I’d have to report their views back to the label, whether it’s what they wanted to hear or not. It was taxing.

“They’d sometimes plan things I wouldn’t find out about ’til it was far too late. It was the same on one occasion when Morrissey was on a train in one direction and the rest of the band were on a train going in the other direction. Morrissey was on a train up to his mum’s and the rest of the band were on a train to London to do a TV show.”

“You’ve got to have a bit of fish, Moz”

Nevertheless, James – who was sacked and then rehired during the summer of 1984 – accompanied the band to America on Concorde for their first US tour. “It was a bit of a waste of money, certainly in terms of vegetarian food. It was far too dainty for them. Their vegetarianism at that point was beans and chips without the sausage. If they’d have been presented with something like a couscous salad, it wouldn’t have gone down well with them.”

Indeed, as the tour wound its way from Chicago’s Aragon Ballroom (June 7) to the 16,000-capacity Irvine Meadows Amphitheatre in California (June 29), the band found it increasingly difficult to maintain a purely vegetarian diet. “I remember arriving in LA and we got picked up by a mini bus,” recalls James. “We left the airport and on Manchester Avenue the next thing we see is ‘English Fish & Chips’.

“It had taken a considerable amount of grief getting everyone onto the minibus, then five minutes later it was all ‘Let’s stop for fish and chips!’ So then we’re all eating fish and chips. I think fish was still acceptable at that point for everyone, although I can’t vouch for Moz. Maybe Moz was put off once, when he was being encouraged to eat fish by our security guy, Jim Connolly. ‘You’ve got to have a bit of fish, Moz.’ When it arrived it still had its head on, and he turned up his nose. I think that was the last time he tried to have fish.”

“I always thought animals were very much like children”

On June 11, The Smiths played LA’s Warner Theatre. In the audience was Dan Mathews, who’d recently begun working for PETA. In his memoir, Committed, Mathews recounts cold-calling Morrissey in his hotel room when, to Mathews’ surprise, the singer agreed to an impromptu interview: “Since this is for the animals, obviously I’m duty-bound,” Morrissey explained. “I always thought animals were very much like children,” he continued. “They look to us to help them and protect them…”

At the conclusion of the interview, Morrissey offered Mathews an unreleased live version of “Meat Is Murder” – recorded at the Apollo Theatre, Oxford in March – for inclusion on a PETA compilation album, Animal Liberation. “In addition to interviewing him a few times we’ve had many dinners and gone out on the town a few times in LA,” says Mathews.

“I also connected with him once in El Paso on tour. Hates spicy food, loves Italian food, hates Madonna, loves [drag performer] Lypsinka, hates parties, loves Champagne, hates sensational news programmes, loves Golden Girls.” (Morrissey continues to support PETA; though no-one interviewed for this article could confirm if he’d actively engaged in dialogue with other animal rights groups).

“They were really at the top of their powers”

“They were great shows,” says Billy Bragg, who supported The Smiths on the US tour. “When you first tour the United States Of America, it’s so exciting. To be part of that with a bunch of guys who were doing that, it was a privilege. They were really at the top of their powers.”

Andy Rourke explicitly cites the band’s first American tour as a turning point in the band as a live entity. “We were changing,” he admits. “We thought we needed to bolster up the sound a bit. So we were all going full throttle. Johnny was using a ton of effects, and four amps at once.”

Noting the differences between UK and US audiences, Stuart James says there were “less bed-sitters” among the US crowds. Rourke elaborates. “The first thing that I noticed, we had a female following in America. Whereas in England it was predominantly pale young boys. The fans used to go crazy in America. A lot more exuberant.”

“We were doing these shows that were blowing people’s doors off,” adds John Featherstone. “It was our first US tour, we did two nights in the Beacon Theatre. In Chicago, we stayed in the Ambassador East, which is the hotel from The Blues Brothers. That was one of the sacred cultural icons of The Smiths. The Blues Brothers, Spinal Tap, Richard Prior…”

“That was Morrissey just trying to poke fun a bit”

Reflecting on how Morrissey responded to America, Billy Bragg recalls: “One thing with Morrissey that’s universal is that he’s an outsider. And where was he more of an outsider at that point than America? But English music at the time had a real credibility in the USA. REM were in a similar sort of groove to The Smiths and had in Michael Stipe another outsider character.”

“As a performer, Morrissey relished the euphoria,” acknowledges Featherstone. “But he took slight offence to the perceived lack of culture in some of the fans. A lot of the US audience, particularly at gigs out west, like San Diego and Oakland, were more ‘Whoo, let’s party.’” Featherstone also recalls the choice of opening act on a number of the dates: transvestites.

“That was Morrissey just trying to poke fun a bit. It was done through the agent. Morrissey came up with the idea, for sure. It was a little more formalised than an open casting call, yeah.” Featherstone laughs broadly at the memory; he also speaks fondly of Johnny Marr’s wedding to his girlfriend Angie Brown in San Francisco. “I remember the Meat Is Murder tour being surrounded by friendship and laughter more than anything else.”

“I was pretty impressed with his taste in luggage”

Asked for an enduring image of Morrissey during the Meat Is Murder period, Dave Harper alights upon the singer’s choice of clothing. “He started to wear a rather large hat, bigger than a trilby. A homburg? Wide-brimmed. And a long overcoat, probably an expensive one. He always had expensive luggage. He bought Rimowa. It was aluminium, almost corrugated; it might have even been a wheelie case. I was pretty impressed with his taste in luggage. He liked having nice, expensive things.”

Hats? Coats? Luxury luggage brands? Clearly, in 1985 Morrissey and The Smiths were going somewhere. A No 1 album. A sell-out tour, including a headline show at the Royal Albert Hall (“each of our families had a private box,” remembers Rourke). But such was the speed at which they were moving, in August, 1985, they returned to the studio to begin work on their third album, The Queen Is Dead.

“They brought vegetarianism into the middle of the debate for young people at the time in a way that nobody else could have done it,” insists Bragg. “Instead of writing a gentle song about loving the animals, going in there like that with a buzz saw, with the sounds of the abattoir in the background, it was a fabulous piece of agitprop.”

“It was a very important record”

The Smiths further reinforced their political agenda by briefly allying themselves with the Red Wedge tour. But Meat Is Murder remains their most enduring statement. “It was a very important record,” reflects Andy Rourke. “It educated a lot of people as to the plight of animals and their mistreatment; the barbarism, literally. What Morrissey and The Smiths have done in terms of promoting vegetarianism is amazing.”

The album’s title song, meanwhile, continues to be a live highlight of Morrissey’s solo sets; still lit with the familiar blood-red wash devised on the 1985 tour. Introducing the song onstage at London’s O2 Arena, on November 29, 2014, Morrissey was moved to cite a story that had recently broken in the UK newspapers. “I read the other day that 75 per cent of chicken sold in the UK is contaminated and therefore poisonous,” he observed. “And I thought to myself: ‘Ha, ha, ha, ha…’”

The post “We were unmanageable!” The making of The Smiths’ Meat Is Murder appeared first on UNCUT.